Austria rebuts heirs' Nazi loot claims for Schiele paintings

VIENNA

Orders to hand back artworks by Austrian painter Egon Schiele to the American heirs of their former Jewish owner have forced some of Austria's top museums to deny claims that some of their holdings were Nazi loot.

The latest in a series of legal bids targets works from the vast art collection of Fritz Gruenbaum, an Austrian Jewish cabaret performer and outspoken critic of the Nazis, who perished in the Holocaust.

His collection comprised more than 400 pieces, including 81 by the Expressionist master Schiele. Overall it would now be worth an estimated 500 million euros (around $540 million), according to Austrian newspaper Der Standard.

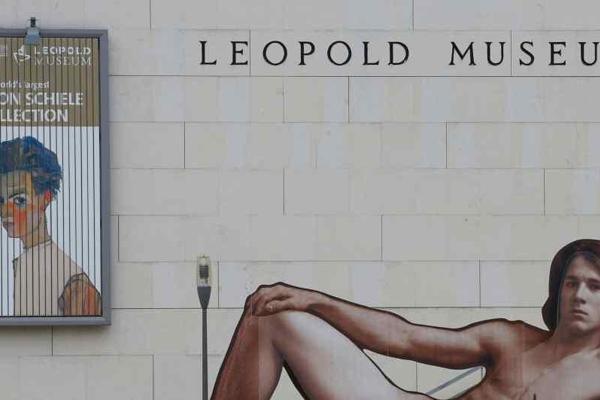

Twelve Schiele pieces from the collection are housed in two Viennese museums - the Leopold Museum has 10 paintings and drawings including Dead City III (1911), while the Albertina has the remaining two.

Gruenbaum's descendants have been demanding their return for more than two decades, saying they were looted by the Nazis.

The Austrian government insists the state obtained them in good faith.

"Despite meticulous research over years, no evidence was found that Fritz Gruenbaum's collection was confiscated" by the Nazi authorities, Austria's culture ministry said in an email sent to AFP.

"On the contrary, the evidence suggests that the collection was still in the family's possession after the end of the Nazi regime," it added.

In 2010, a special commission recommended that it should not return the artworks.

The government said Gruenbaum's sister-in-law Mathilde Lukacs sold dozens of works to a Swiss art dealer in the 1950s.

The dust settled until several lawsuits in the United States came to a different conclusion.

US restitution claims

America's Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery (HEAR) Act from 2016 extended the statute of limitations for recovering Nazi-looted artworks, allowing Gruenbaum's heirs to return to the courts.

Aiming to win restitution, they first pursued several Schiele drawings exhibited in the United States.

They said Gruenbaum's collection was stolen by the Nazis, and largely auctioned or sold abroad to fund the Nazi Party. In 2018, a New York judge ruled in their favor.

Since then, one restitution after another followed, with some museums such as New York's Museum of Modern Art returning them voluntarily and others waiting for a court order.

In late January, US authorities said they had been able to return 10 artworks "looted by the Nazis" to Gruenbaum's descendants, valued at a minimum of 11 million euros.

In December 2022, the heirs filed a complaint against Austria in New York, accusing the country of having "unjustly and unlawfully enriched" itself "at the expense" of the descendants.

The Austrian government's position that there was no evidence the paintings were looted also includes the works that have "recently been voluntarily restituted in the US," the culture ministry email said.

It says even those artworks reached the art market legally via Lukacs.

The Klimt precedent

In other cases, the Alpine country of 9.1 million inhabitants has so far returned about 15,800 artworks to the heirs of their former Jewish owners.

The stakes are especially high for the Leopold Museum, which houses the world's largest collection of Schiele's work.

Opened in 2001, the museum is the brainchild of visionary collector Rudolf Leopold.

He began buying up paintings by Schiele and the Austrian symbolist master Gustav Klimt in the aftermath of World War II, at a time when they had been largely forgotten.

In 2016, it returned two Schiele drawings to the descendants of Jewish art collector Karl Maylaender, who was deported from Austria in 1941.

The Albertina also returned five drawings from the same collection in 2011.

In one of the most spectacular legal battles, an American claimant sought five masterpieces by Klimt from Austria's Belvedere Museum.

The museum was forced to return the works and they were later auctioned off for a record sum of 328 million euros.