Alexander and legends of the Middle East

Niki GAMM

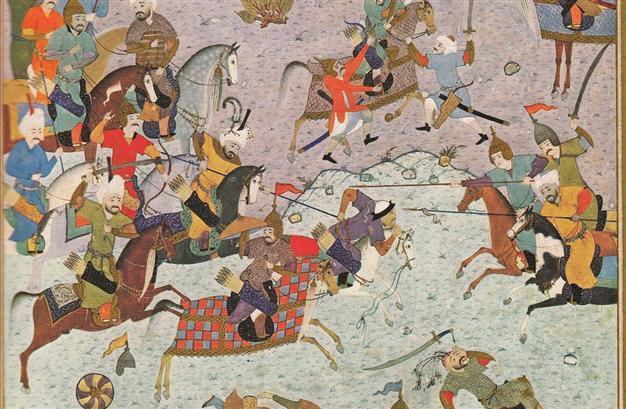

Iskander in Battle against Darius.

Alexander the Great became a legend with his passing in 323 B.C. and one of the greatest legendary figures of all time from the classical era to today. Historian and author Harold Lamb has written, “No other man has been claimed – in legends – by so many nations: Egyptian fable makes him a god; Arabo-Persian tradition has Iskander a hero-saint; Israelite lore joins him to the house of David as a precursor of the Messiah; even Ethiopian hagiology preserves his memory as a saint; medieval Christian tales relate how Alixandre le Grant searched for paradise.”The so-called Alexander Romance began with a collection of the legends swirling around him. These were compiled in Greek by an author named Pseudo-Callisthenes, not to confuse him with an earlier author named Callisthenes who happened to be the nephew of Alexander the Great, in the third century A.D. in Alexandria, Egypt. According to one scholar, the original text no longer exists but it can be shown as “the source of some 80 different versions written in 24 different languages.” Among these languages were Syriac, Armenian, Persian, Arabic, Ethiopic and Bulgarian. The Greek was translated into Latin quite early on and then into the vernacular languages in Europe where it enjoyed popularity throughout the Medieval period.

Alexander becomes super human

The Alexander Romance shows Alexander in a magical light and surrounded from conception onward by signs that he would rule the known world of his time, the mid-fourth century B.C. as a great king. He even had dealings with the gods. At the same time, the way in which he is presented is not beyond the ability of the contemporary but ordinary man to understand. It was written for people who believed in magic and the powers of the gods and it paralleled their customs and lifestyle while providing historical fact. “The author attempts to show the importance of Alexander and his life in a way that the common person can understand. It provided a story that was able to match the many deeds that he performed while he was alive and connects the events so that the reader can relate to them.” For example the person who was to follow King Philip II of Macedonia on the throne was supposed to be the only person who could tame a killer horse named Bucephalus. Alexander walked up to the horse and was immediately able to mount and ride it which no man had previously been able to.

Given the close ties among the countries of the eastern Mediterranean, the Alexander legends became incorporated in Jewish traditions. He was originally portrayed as a vainglorious king but this changed when it couldn’t be reconciled with his success. A just, all-powerful God wouldn’t permit such success to a wicked ruler. So his image was transformed into one of that suited Jewish traditions, one in which he accepted the truth of the Jewish religion even if he himself didn’t believe in Judaism.

For Christians, it became easy to change Alexander so that in some stories he became a saint or at least someone who believed in monotheism. Over time the legendary Alexander became involved with biblical stories. The most prominent of the many legends is that of Alexander ascending into heaven, descending into the depths of the sea in a bubble, searching for the Water of Life in the Land of Darkness and building a wall at the end of the earth to prevent Gog and Magog from bringing evil into the civilized world and then devouring it as a precursor of the end of the world. When the stories take place in the western part of the Middle East, Alexander is supposed to have had Socrates as his companion and when he’s in the east, he travels with Khidr (Hizir in Turkish), the green man.

From there it is not surprising to find him entwined in Islamic traditions. Scholars have actually identified the king who is known as Dhul-Qarnayn (of the Two Horns) with Alexander the Greek turning him into Iskandar Dhul-Qarnayn or Alexander of the Two Horns. Philologists have agreed, although there are those who find this identification somewhat debatable. There are as well coins from Egypt that depict the head of Alexander with two horns, a sign that he was a god on a level with Egyptian gods.

In the Qur’an (Al-Kahf: 83-101), Dhul-Qarnayn travels, first one way and then another. The people he meets on the second route beg him to build a wall between them and Gog and Magog who are “doing mischief in the land.” The Qur’anic story opens up speculation as to where this wall built of iron might actually be. The Islamic scholar, Maulana Muhammed Ali, in his commentary to his English translation of the Qur’an, dismisses the claim that Dhul-Qarnayn is Alexander. He believes that the reference is to a story in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible in which the two horns refer to the kingdoms of the Medes and the Persians (550–330 BC). In his opinion that would originally make Gog and Magog into barbarians who lived to the north of these two kingdoms between the Black Sea and the Caspian and identifies them as Scythians who dominated the western and central steppe lands of Eurasia in the first millennium BC. So where was the wall that was supposed to have been built? The Qur’an says it was between two mountains and made of blocks of iron. Muhammed Ali decided that it must have been in Daghestan on the western shores of the Caspian.

The Bulgars on the Volga converted to Islam in the 10th century and adopted the story of Iskander Dhul-Qarnayn. He is supposed to have built the iron walls somewhere in their territory as a defense against the tribes of Central Asia. As well he was appropriated to become the ancestor of the rulers of Bulghar, a city which he was believed to have founded.

Of course it was natural that the Alexander Romance would become part of Persian literature as the Iskandarnamah. The Persians, in spite of their enmity against him for conquering their country, created a genealogy in which his mother was a concubine to Darius II and making Alexander a half-brother of the last Persian ruler. He became the subject of epic poems by the 12th century. One of the greatest Persian poets, Nizami, wrote one on the romantic histories of Alexander in the 12th century.

From the Persians, the Iskandarnamah became the Iskendername in Turkish. The fourteenth poet Ahmedi composed one and it became the first important secular poem of the western Turks as E.J.W. Gibb describes it in his History of Ottoman Poetry. Other Ottoman poets also wrote on the same subject but few are considered to have rivaled Ahmedi.