African leaders met on July 7 to launch a continental free-trade zone that if successful would unite 1.3 billion people, create a $3.4 trillion economic bloc and usher in a new era of development.

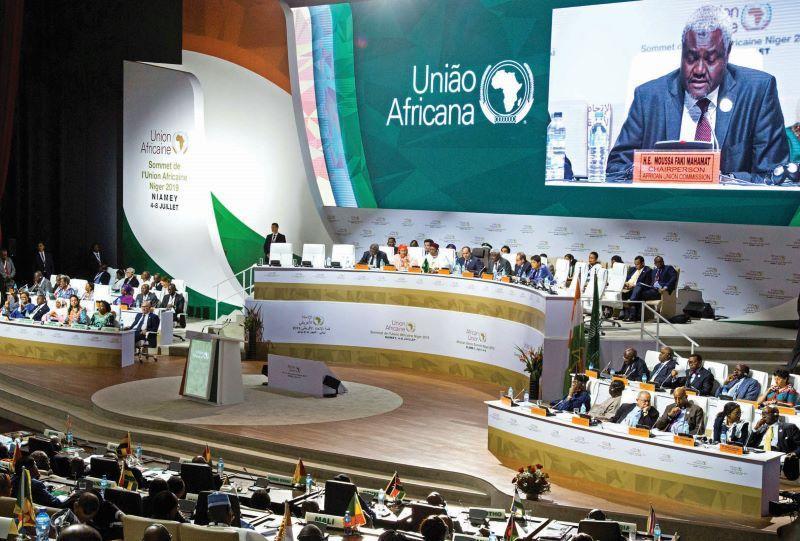

After four years of talks, an agreement to form a 55-nation trade bloc was reached in March, paving the way for July 7's African Union summit in Niger.

It is hoped that the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), the largest since the creation of the World Trade Organization in 1994, will help unlock Africa’s long-stymied economic potential by boosting intra-regional trade, strengthening supply chains and spreading expertise.

“The eyes of the world are turned to Africa,” Egyptian President and African Union Chairman Abdel Fattah al-Sisi said at the summit’s opening ceremony.

AfCFTA “will reinforce our negotiating position on the international stage. It will represent an important step.”

Africa has much catching up to do: Its intra-regional trade accounted for just 17 percent of exports in 2017 versus 59 percent in Asia and 69 percent in Europe, and Africa has missed out on the economic booms that other trade blocs have experienced in recent decades.

Economists say significant challenges remain, including poor road and rail links, large areas of unrest, excessive border bureaucracy and petty corruption that have held back growth and integration.

Members have committed to eliminate tariffs on most goods, which will increase trade in the region by 15-25 percent in the medium term, but this would double if these other issues were dealt with, according to International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates.

‘Economic game changer’

The IMF in a May report described a free-trade zone as a potential “economic game changer” of the kind that has boosted growth in Europe and North America, but it added a note of caution. “Reducing tariffs alone is not sufficient,” it said.

Africa already has an alphabet soup of competing and overlapping trade zones: ECOWAS in the west, EAC in the east, SADC in the south and COMESA in the east and south.

But only the EAC, driven mainly by Kenya, has made significant progress towards a common market in goods and services.

These regional economic communities (REC) will continue to trade among themselves as they do now. The role of AfCFTA is to liberalize trade among those member states that are not currently in the same REC, said Trudi Hartzenberg, director at Tralac, a South Africa-based trade law organization.

The zone’s potential clout received a boost last week when Nigeria, the largest economy in Africa, agreed to sign the agreement at the summit. Benin has also since agreed to join. Fifty-four of the continent’s 55 states have signed up, but only 25 have ratified.

One obstacle in negotiations will be the countries’ conflicting motives.

For undiversified but relatively developed economies like Nigeria, which relies heavily on oil exports, the benefits of membership will likely be smaller than others, said John Ashbourne, senior emerging markets economist at Capital Economics.

Nigeria’s concerns

Nigerian officials have expressed concern that the country could be flooded with low-priced goods, confounding efforts to encourage moribund local manufacturing and expand farming.

In contrast, South Africa’s manufacturers, which are among the most developed in Africa, could quickly expand outside their usual export markets and into West and North Africa, giving them an advantage over manufacturers from other countries, Ashbourne said.

The vast difference in countries’ economic heft is another complicating factor in negotiations. Nigeria, Egypt and South Africa account for over 50 percent of Africa’s cumulative GDP, while its six sovereign island nations represent about 1 percent.

“It will be important to address those disparities to ensure that special and differential treatments for the least developed countries are adopted and successfully implemented,” said Landry Signe, a fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Africa Growth Initiative.