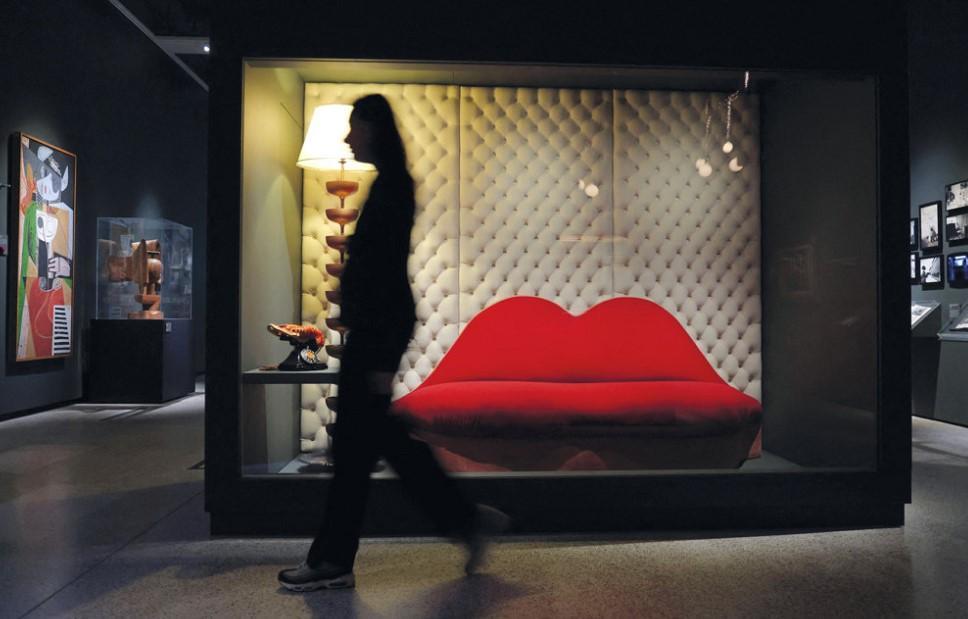

From Salvador Dali’s lip-shaped sofa to the dreamlike video clips of Icelandic artist Bjork, Surrealism has influenced design for almost a century.

The complex evolution is now being explored in an exhibition, “Objects of Desire: Surrealism and Design 1924 – Today” at London’s Design Museum.

Visitors are welcomed upon arrival by one of the most notorious depictions of the human psyche: “Metamorphosis of Narcissus,” painted by Dali in 1937.

The Spanish painter’s entire oeuvre was influenced by theories on the subconscious, in particular by Sigmund Freud’s

“The Interpretation of Dreams,” which he read while studying in Madrid in the 1920s.

Through his British patron Edward James, Dali met the Austrian neurologist in London in 1938. The exhibition begins with the fruit of Dali and James’s close collaboration.

Dali created numerous pieces of iconic future for the British poet and patron such as a lobster-shaped telephone, a lamp stand made of champagne glasses, a chair with human arms, and a sofa shaped like the lips of actress Mae West.

But even before Dali, early 20th-century modernist architect Antoni Gaudi had already tried “to give objects which could be purely functional, an emotional kick and a psychological impact through this sort of changing form to something much more organic and emotional,” said curator Kathryn Johnson.

Born in literature before spreading to visual art, Surrealism declined as an artistic movement in the early 1950s but it survived in design.

In fact, some of its creations “seem to have really found their moment in this century,” Johnson told AFP.

Such was the case for a broken-foot lamp commissioned from Dali in 1937, which was considered too avant-garde for the market at the time and it wasn’t until 2019 that the lamp was manufactured.

The exhibition features a huge lamp on a plastic horse by Swedish studio Front (2006) and an armchair made of Disney stuffed animals created by Brazilians Fernando and Humberto Campana (2007).

Two lamps made of horsehair by British artist Jonathan Trayte (2022) also go to show “unexpected design” in everyday objects.

Dali collaborated with Walt Disney in the 1940s and Christian Dior in the 1950s, helping Surrealist contributions to continue to the present day.

During the pandemic, young British-Nigerian couturiere Yasmina Atta designed garments inspired by Afro-Surrealism, such as a woolen top with butterfly wings which can be electrically activated.

“She made it during lockdown, and I think it captures that feeling of trying to fly away from us being stuck in one place,” Johnson said.

The exhibition argues that Surrealism, a reaction to the horrors of World War I and the 1918 flu pandemic, has undergone a resurgence in turbulent times.

“It’s no accident that these moments coincide with periods of economic and political instability, because surrealism was founded on a creative embrace of chaos, it accepts uncertainty, the inexplicable, and I think we need it now”.

Music videos of songs such as “Utopia,” “Mutual Core” and “Hidden Place,” made by Bjork between 2001 and 2017 - show dreamlike relationships between humans, nature and technology.

According to Johnson, even strange images generated by artificial intelligence “can result in different kinds of art.”

“Artificial intelligence is modelled on the way that the brain works, and it doesn’t surprise us that it can be creative, but it’s fascinating to see how that may play out in the future,” she added.

Despite the exhibition’s inclusion of iconic photographs such as Man Ray’s “Le violon d’Ingres” (1924), Mateo Kries, director of the German Vitra Design Museum which loaned many pieces to the show, said that today Surrealism is, “no longer an art movement but an attitude that you can have towards art or design.”