Will the AKP pay for the graft scandal in the elections?

I have been working non-stop since the end of May.

I have been working non-stop since the end of May.As a self-declared chapull-Jew (pronunciation of çapulcu, or marauder), I have been blemishing the Justice and Development Party (AKP) relentlessly by writing in my columns, and telling everyone in my path, from hedge funds to foreign journalists, that the economy is looking more and more like a Shakespearian tragedy. I even did my share to blow up the graft scandal by telling the tale of the Fatih Municipality whistleblower.

An article that appeared in Turkish daily Radikal on Dec. 31, 2013, gave me hope that my efforts could pay off. By looking at general and local elections in the last three decades, the article argues that Turkish voters punish corruption at the polls. The evidence presented is quite convincing, but my spider senses urged me to look a bit deeper.

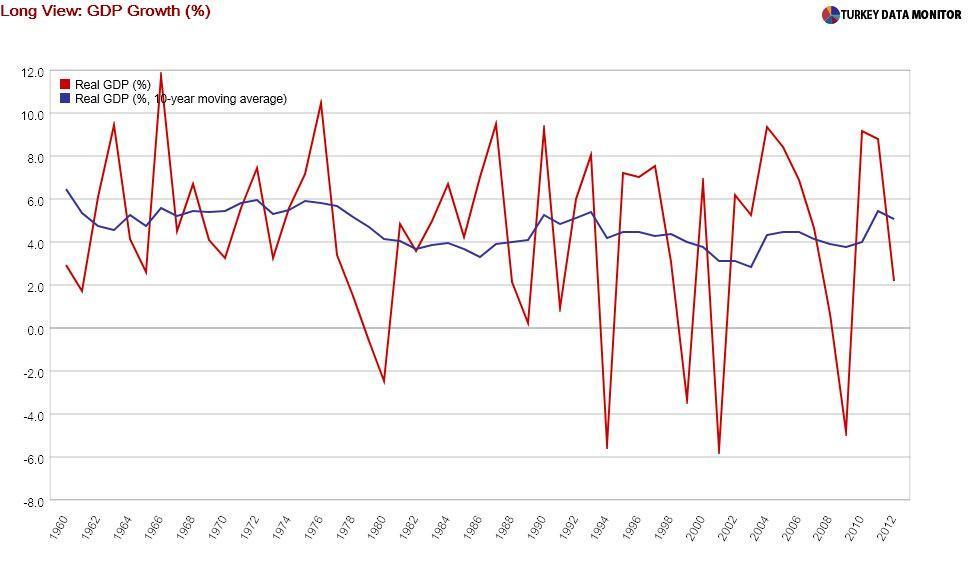

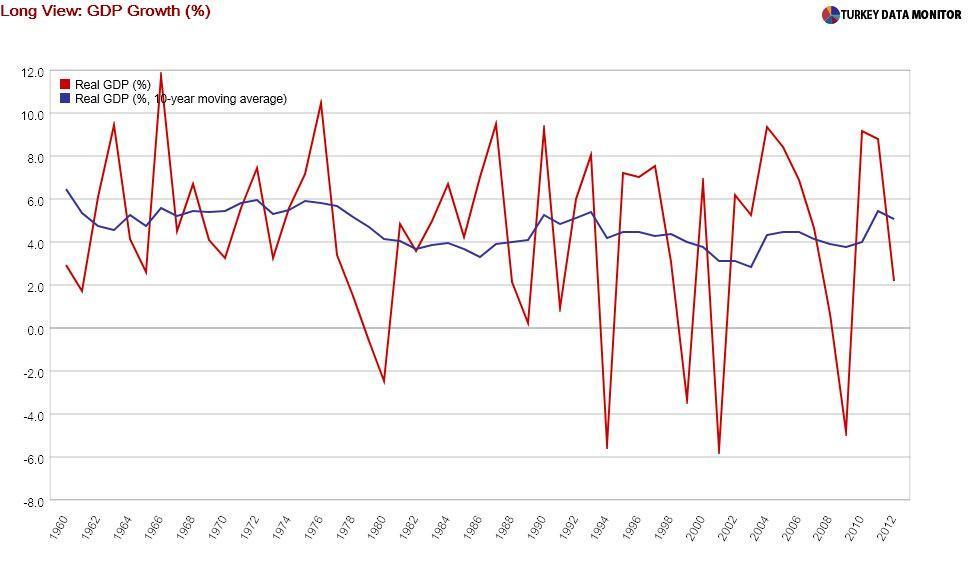

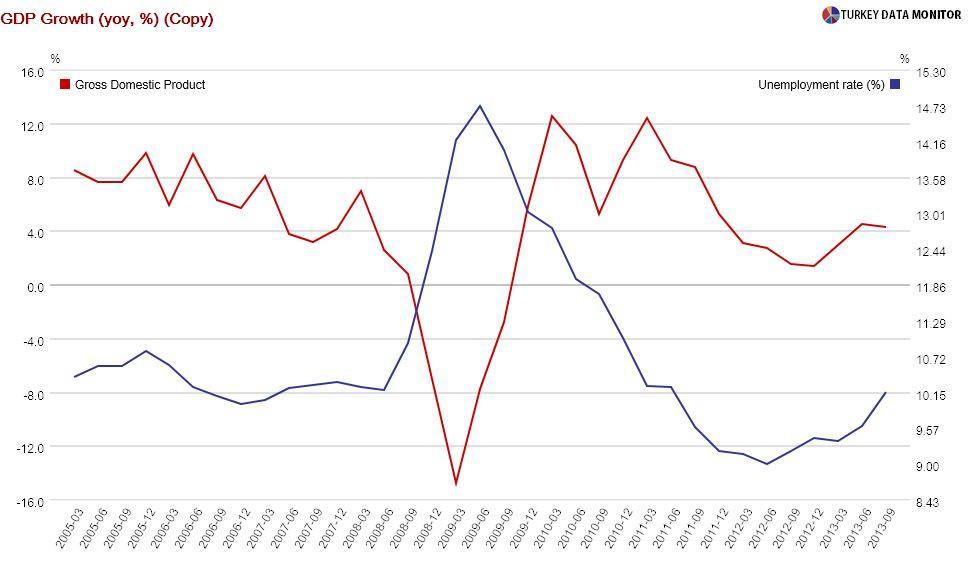

It turns out most of the elections mentioned in the article were during years when the economy did not perform well, so voters could be punishing economic mismanagement rather than corruption. In fact, the 1994 local and 2002 general elections were in the midst or aftermath of major crises. Remember that the AKP’s votes fell from 47 percent in 2007 to 39 percent in 2009, when quarterly growth hit rock bottom and unemployment reached its peak.

Speaking to the Hürriyet Daily News’ own Barçın Yinanç, Professor Ersin Kalaycıoğlu of Sabancı University notes that conservative Turkish voters have so far been indifferent to corruption if the economy is OK. He explains that “most of these people have come from a very long past of relations with the center which they considered corrupt anyway.”

Summarizing his recent research at the Washington Post, New York University political scientist Joshua Tucker argues indifference to corruption is common in countries where graft is prevalent. He and his co-author look at two surveys, one from Sweden, the other from Moldova, where respondents were asked how they would vote in a hypothetical local election if economic conditions had improved or got worse as well as if the mayor was corrupt or fighting corruption.

In Sweden, voters punished the corrupt incumbent regardless of economic conditions, but in Moldova, the mayor was reprimanded only when the economy was not doing well. Tucker then goes on to argue, based on Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) rankings, that the graft scandal could cost the AKP.

I emphasized the deficiencies of the CPI in my last column, and I believe Tucker is underestimating the prevalence of corruption in Turkey. Besides, another recent paper finds evidence in Mexico that corruption information reduces voter turnout as well as both the incumbent and challenger’s votes.

I guess I should start working for the interest rate lobby, a coalition of Jewish financiers and foreign journalists who were recently joined by the United States and Klingon Empire, trying to suck Turkey dry by raising interest rates. It seems crashing the economy is the only way I can get Erdo-gone.