Why has the AKP been so successful?

The Justice and Development Party (AKP)

scored a huge victory in Turkey’s general elections on Nov. 1, garnering almost half of the votes and increasing its vote over the June 7 elections by almost 9 percentage points.

However, my title refers to the last 13 years. After all, except in its first elections in 2002, the AKP has fallen below 40 percent only once, during the March 2009 local elections. While President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s

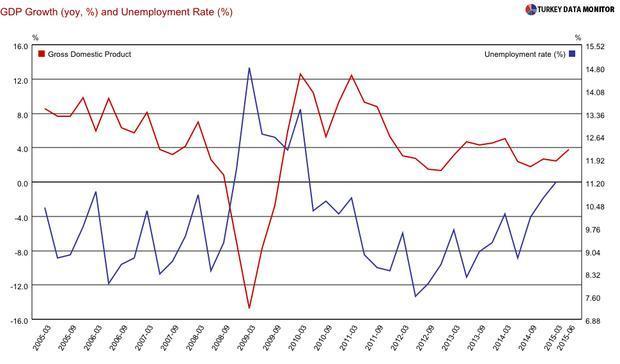

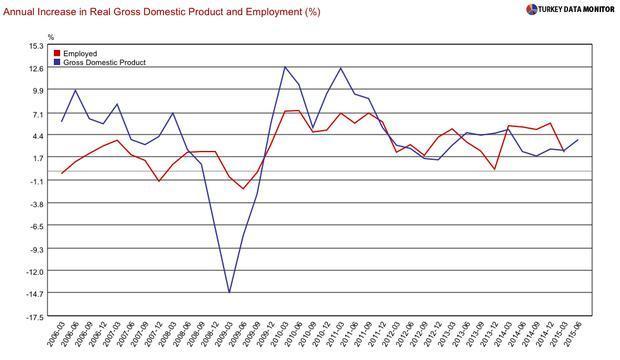

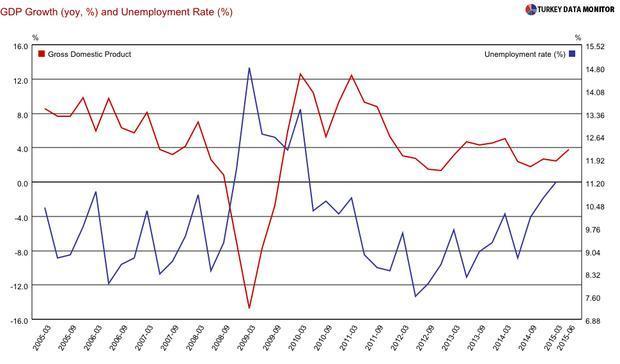

warmongering, the Kurdish terrorist group the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant’s (ISIL) attacks and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) all played their part this time, the party’s economic management is usually given as one of the leading reasons for its recurring success. In fact, growth hit bottom and unemployment peaked,

exactly in March 2009.

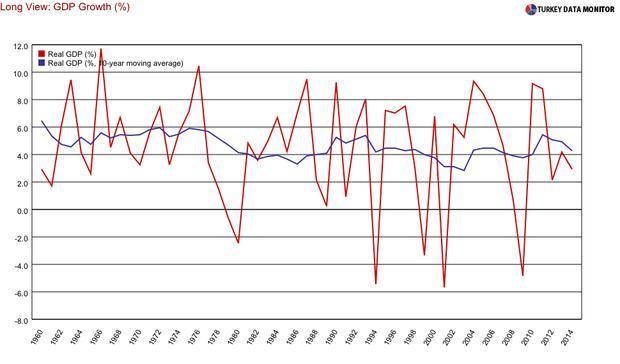

With the continuation of the sound economic program designed by Kemal Derviş, economy czar at the time, and the IMF under the AKP, growth was 7 percent on average from 2002 to 2007 before falling during the following years. As I have argued before, the AKP could not come up with a new storyline, and enact the much-needed

structural reform agenda, once the IMF program expired.

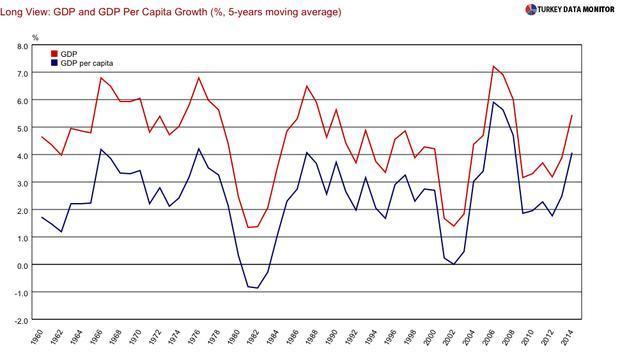

Harvard’s Dani Rodrik has

shown that Turkish growth was in line with that of peers’ from 2002 to 2007, and lower afterwards. A new book by the Independent Social Scientists (BSB) initiative questions the success story further by noting that Turkey did not grow more than that in earlier periods either. The first chapter of “The State of Labor under the AKP” argues that economic performance looks even worse when other macroeconomic indicators are taken into consideration.

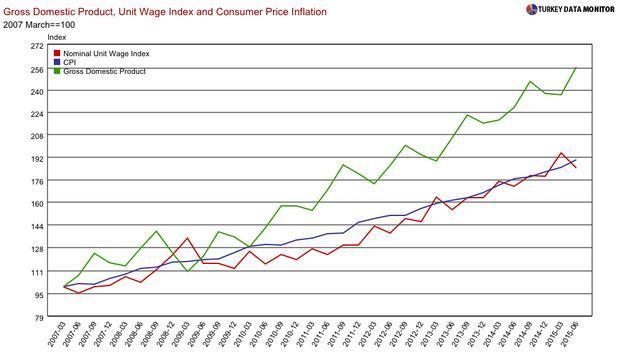

You could argue that the average citizen does not care about growth or the current account, or even inflation, but how she, her family, relatives and friends are doing. The BSB shows that, contrary to popular perception, laborers have

not been particularly better off under the AKP. While wage growth trailed inflation in the early years of the AKP, the gap has closed in the last couple of years. However, the rise in wages and employment has been less than GDP growth.

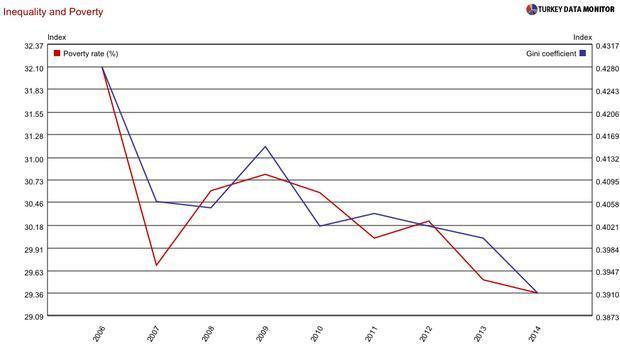

How about the distribution of income and wealth? The improvement in inequality and poverty in the early years of the AKP has

come to a halt. According to Credit Suisse’s

2015 Global Wealth Report, the Turkish middle class has shrunk by half a million since 2000. And while many have risen out of poverty, half of Turkish children are still

under severe material deprivation, and the education system is

marked by inequality. I do not agree with the BSB that the AKP’s health policies were a failure, but the AKP would not have been able to garner so much support on those alone.

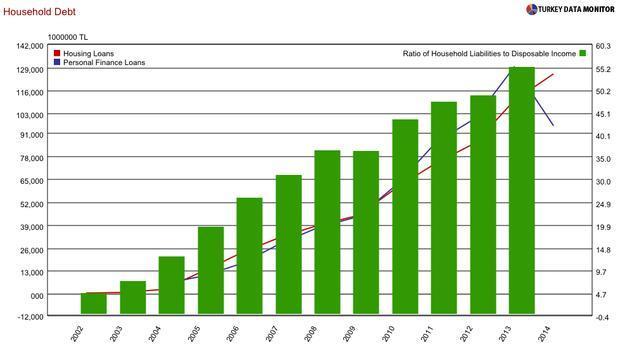

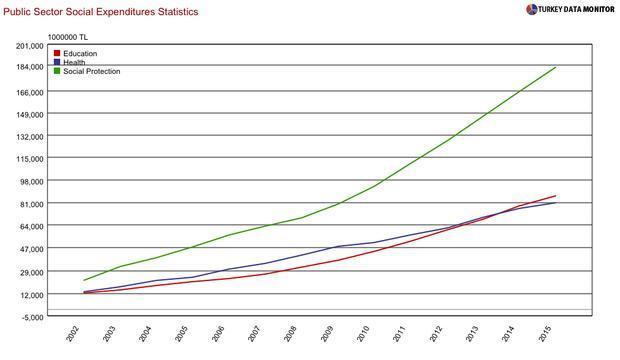

So how come the AKP’s economic management is perceived to be successful? For one thing, the BSB show that consumption has boomed thanks to low-interest loans, with many able to buy white goods, cars and houses for the first time. Moreover, they document that social expenditures, while still being below the OECD and EU averages, have

not only increased, but also been well-targeted – even though they were not enough to counteract the disproportionate burden of indirect taxes on the poor.

As I have been arguing, the spending-led growth financed by cheap foreign money is about to come to a halt, and many will painfully notice debts will have to be repaid. It will be interesting to see if the AKP’s social support system will continue to keep voters happy.

The Justice and Development Party (AKP) scored a huge victory in Turkey’s general elections on Nov. 1, garnering almost half of the votes and increasing its vote over the June 7 elections by almost 9 percentage points.

The Justice and Development Party (AKP) scored a huge victory in Turkey’s general elections on Nov. 1, garnering almost half of the votes and increasing its vote over the June 7 elections by almost 9 percentage points.