Turkish monetary policy has turned into Seinfeld

Yesterday’s rate-setting meeting of the Turkish Central Bank was “about nothing,” just like the 90s hit comedy show Seinfeld. It was “about nothing” to such an extent that I was able to write this column in the airport even before the meeting, having arrived from Johannesburg early in the morning.

Yesterday’s rate-setting meeting of the Turkish Central Bank was “about nothing,” just like the 90s hit comedy show Seinfeld. It was “about nothing” to such an extent that I was able to write this column in the airport even before the meeting, having arrived from Johannesburg early in the morning.It’s not because only two of the twenty-one economists in business channel CNBC-e’s survey were expecting a rate cut. Even those two were predicting that the Bank would lower its marginal funding rate, which is the ceiling of the bank’s interest rate corridor, by 0.25 percentage points and leave the more relevant policy rate intact.

It’s not because monetary policy is not relevant for Turkey anymore, either. On the contrary, the country’s challenging inflation outlook and the weakening lira mean that the Bank needs to adopt a tight stance. That’s why economists were expecting the Bank to stay on hold at yesterday’s rate-setting meeting.

But it was “about nothing” mainly because monetary policy has been rendered ineffective. In introductory economics courses, students learn about the traditional channels through which a central bank can affect inflation and exchange rates. Higher interest rates lower inflation by curbing demand. They also make the local currency more attractive to foreigners, and the resulting capital flows appreciate it.

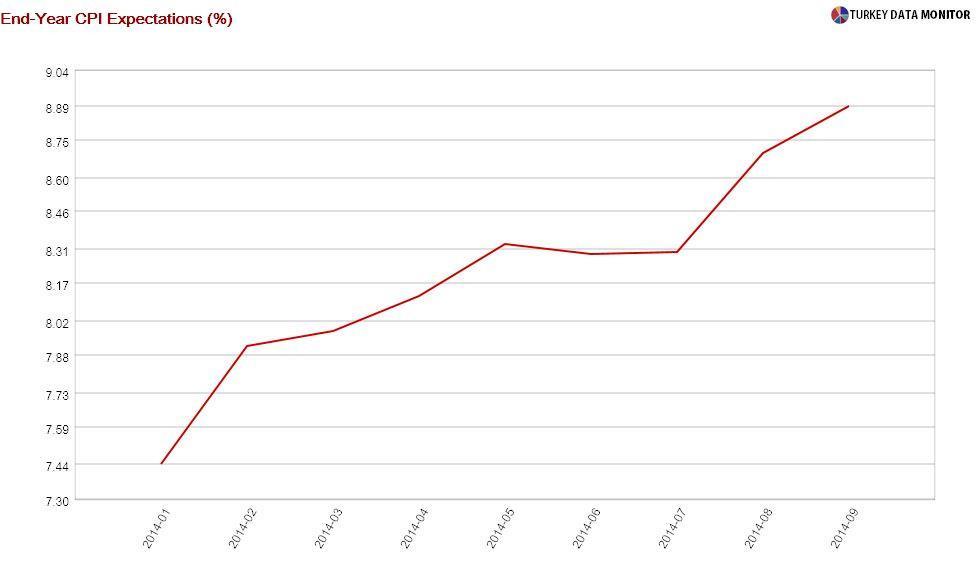

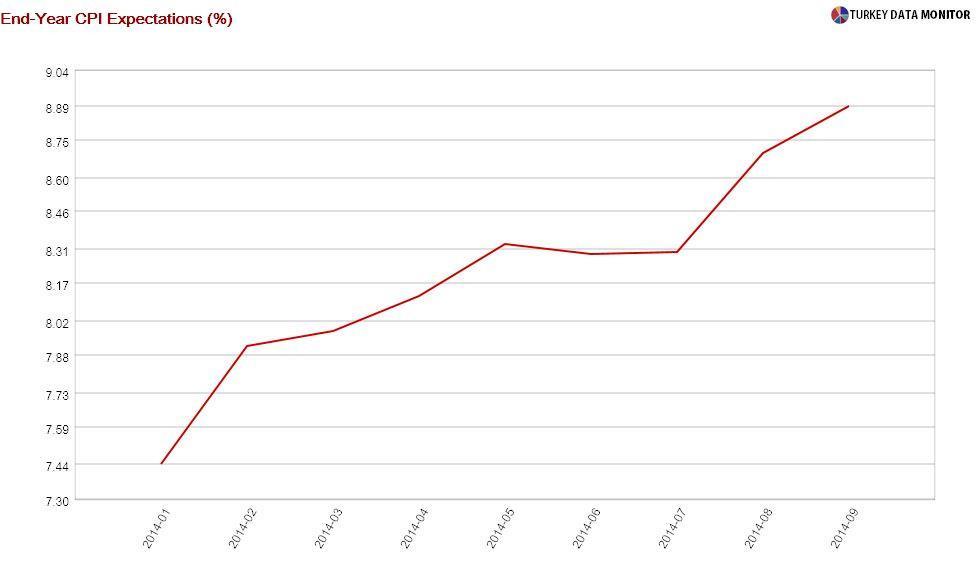

Another channel is credibility, which is very difficult to earn, but equally easy to lose. If no one believes in the Central Bank’s resolve to fight inflation, firms will raise their prices and workers will demand wage increases higher than the Bank’s inflation outlook, which will be impossible to attain as a result. End-year inflation expectations in the Central Bank’s monthly survey, which have been adjusted up throughout the year, are indeed much higher than the Bank’s target.

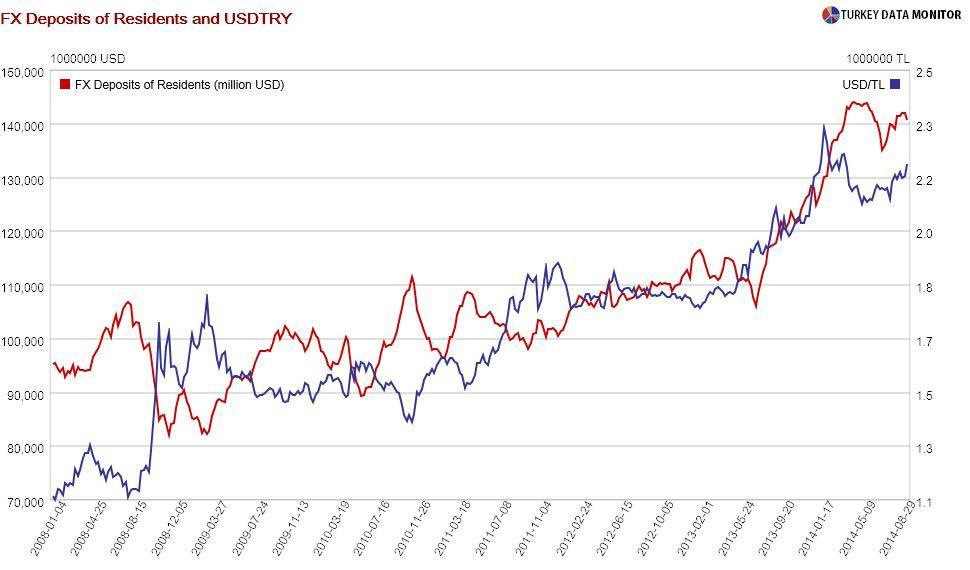

Lack of confidence in monetary policy has also affected the Turks’ foreign currency (FX) decisions. Lira depreciation used to be an opportunity to sell FX, which would act as a buffer against excessive lira weakness. Similarly, lira appreciation would be used as a buying opportunity. As a result, the exchange rate and residents’ FX deposits used to be mirror images of each other.

This relationship broke down around May of last year. First the U.S. Federal Reserve’s announcement that it would start tapering its bond purchases, then the Gezi protests, then the start of tapering and the graft scandal, caused Turks to hoard FX despite a weakening lira, which caused the domestic currency to weaken further.

The Central Bank’s sharp interest rate hike at the end of January could have broken this vicious circle. FX deposits fell for several consecutive weeks during the spring and summer despite a stable currency. But as the Central Bank started cutting rates again, FX deposits started creeping up. As long as Turks expect a weaker lira, keeping rates on hold is not likely to change this trend.

As I put the finishing touches to the column, the Central Bank did not surprise: All the rates were kept constant. Maybe, I would have been better off writing on the economics of poaching rhinos, which is much more interesting than the Central Bank’s rate-setting decision.