Turkey’s employment-generating growth

Speaking at the – closed to the press, but your friendly neighborhood economist has eyes and ears everywhere – “Bonds, Loans & Sukuk Turkey” conference in Istanbul on Nov. 13 and 14, both Deputy Prime Minister (and economy czar) Ali Babacan and Finance Minister Mehmet “nominal” Şimşek emphasized that growth has been employment-generating.

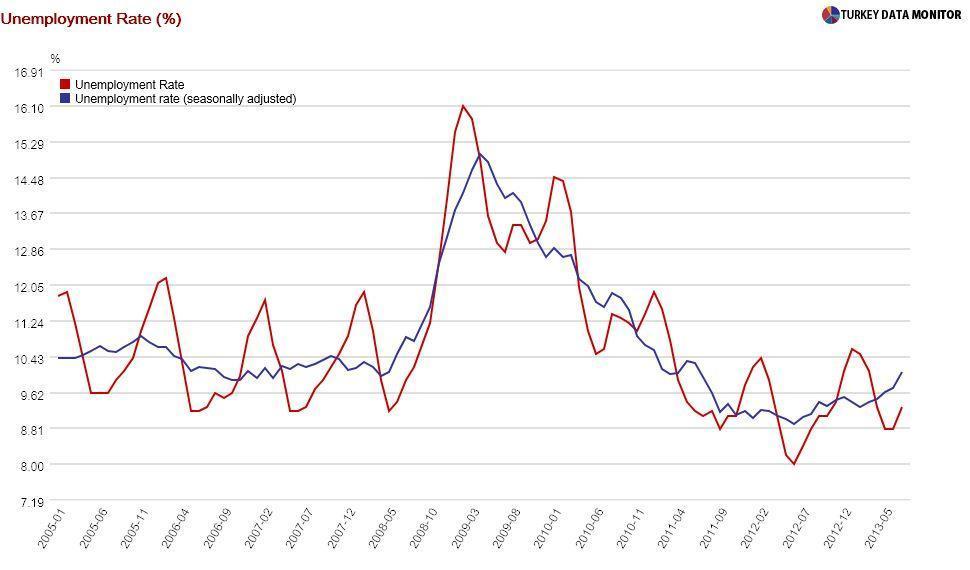

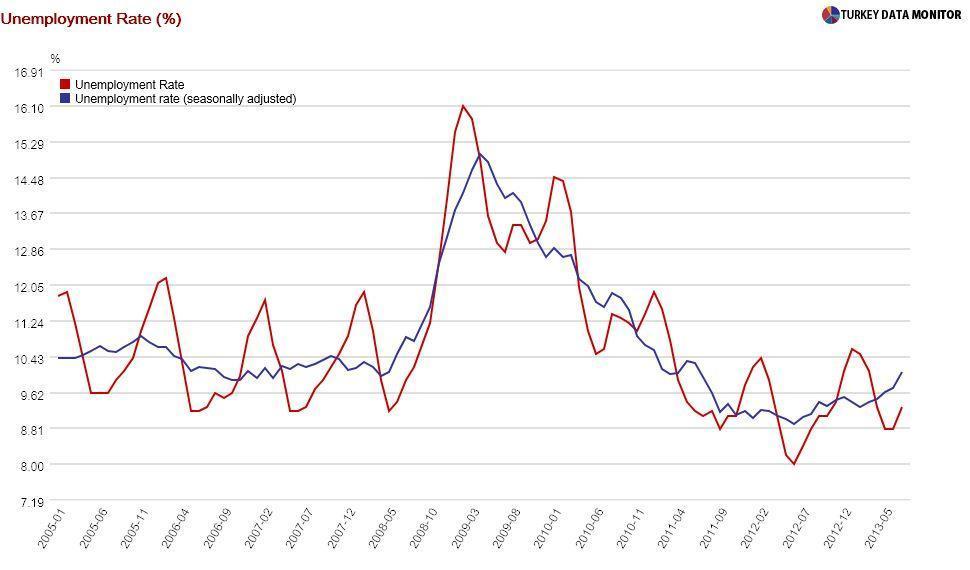

Speaking at the – closed to the press, but your friendly neighborhood economist has eyes and ears everywhere – “Bonds, Loans & Sukuk Turkey” conference in Istanbul on Nov. 13 and 14, both Deputy Prime Minister (and economy czar) Ali Babacan and Finance Minister Mehmet “nominal” Şimşek emphasized that growth has been employment-generating.A casual look at labor force statistics would prove them right. There is a lot of seasonal employment in Turkey, especially in sectors such as agriculture, construction and tourism, so it is better to weed out seasonality from the statistics. After peaking at 15 percent in April 2009, seasonally adjusted unemployment rate hit a long-time low of 8.9 percent in June 2012 despite steady growth in the labor force during this period.

The strong economy certainly created jobs, but employment gains were even stronger than the growth figures would suggest. This point was explained by Bahçeşehir University think-tank Betam’s director, Seyfettin Gürsel, during the panel Strategies for Increasing Employment and Labor Market Efficiency in the Izmir Economic Congress.

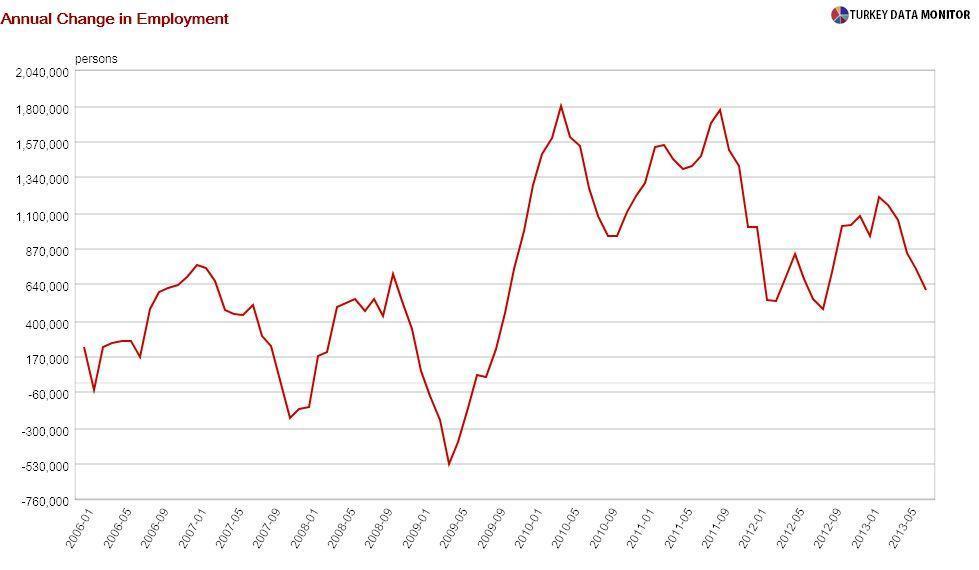

From 2004 to 2008, annual growth was 5.1 percent, whereas employment rose by 390,000 on average. In other words, we got 76,000 new jobs for each percentage point of growth. From 2010 to 2012, on the other hand, the corresponding figures were 5.4 percent and 1,100,000, which would translate to 204,000 jobs for each percentage point of growth.

By the almost continuous rise in unemployment since June 2012, you could think the trend has been reversed. Nothing could be further from the truth. While third-quarter national income accounts are to be released on Dec. 10, the economy grew 2.6 percent annually during the four quarters before. Employment rose by 742,000 during this period. Using Gürsel’s back-of-the-envelope calculation, 290,000 jobs were created for each percentage point of growth.

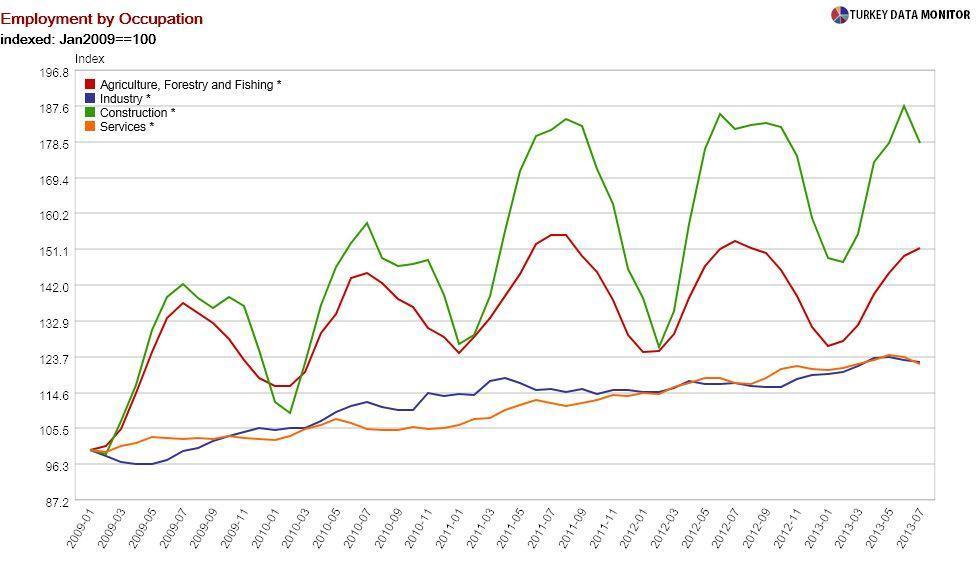

I will leave the reason(s) behind this employment-generating growth to a future column, but I have to mention that employment gains have been the strongest in construction, which could explain the government’s obsession with the sector. I should also note that Babacan and Şimşek are only telling half of the story. These rises in employment did not come without a cost: Labor productivity has fallen.

The important question is whether growth will continue to be employment-generating in the near future. I doubt it. For one thing, although labor force statistics lag behind more than two months (the latest numbers are from July), annual gains in employment have started to fall by a lot of late. In any case, as confirmed by the rise in unemployment since mid-2012, 3-3.5 percent growth is not enough to lower unemployment.

That’s why I will devote as much attention to August labor statistics as the October budget, both of which will be released today. In fact, the budget figures will probably be a function of employment during the remainder of the year and in 2014.