Turkey: Navigating the road to sustainable growth

That was the title of the seminar organized by the Economic Research Forum at Koç University on Dec. 5, where I was one of the two speakers. I clarified right at the beginning that the dependence of growth to external financing made it unsustainable.

That was the title of the seminar organized by the Economic Research Forum at Koç University on Dec. 5, where I was one of the two speakers. I clarified right at the beginning that the dependence of growth to external financing made it unsustainable.

Moody’s claimed, in its latest reports on the country, the impact of the Fed’s tapering of its bond purchases on the Turkish economy would be limited, but the question is not whether Turkey will have a major crisis like 2001. It surely won’t. However, I don’t think the country could grow 5 percent without capital flow, which would mean it would get stuck at the dreaded middle-income trap.

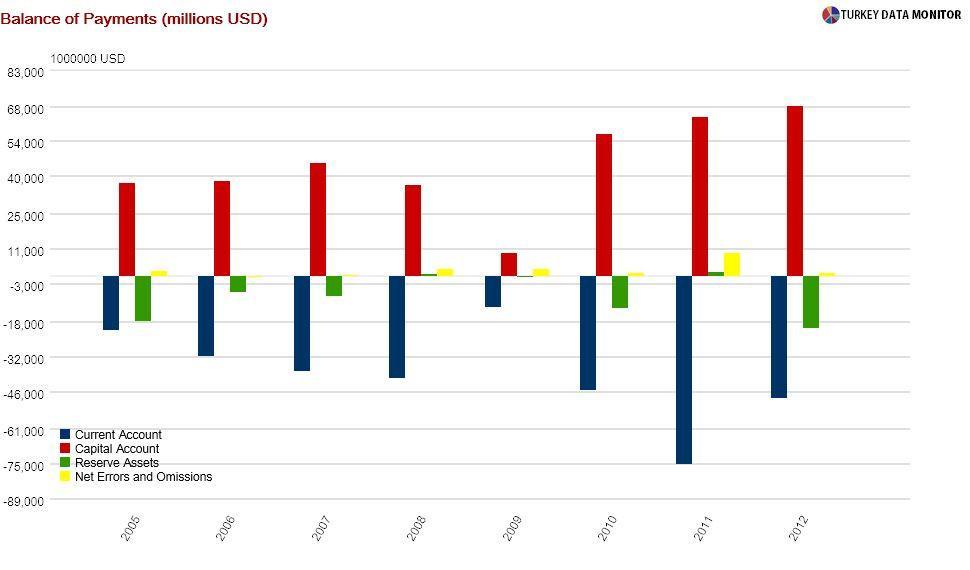

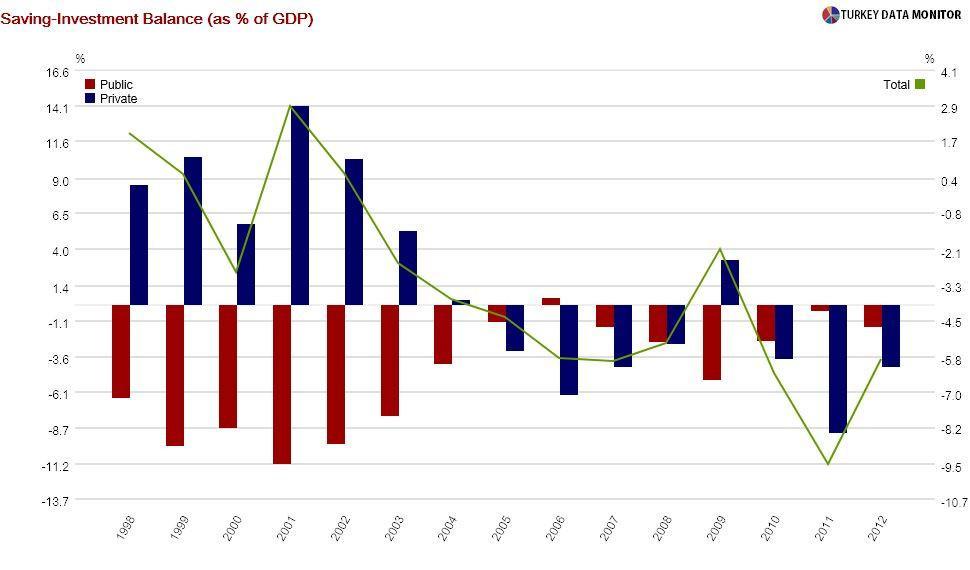

The obvious solution would be to reduce the country’s current account deficit, which requires this large external financing. National income accounting identities dictate that the deficit is equal to the private and public savings investment gaps.

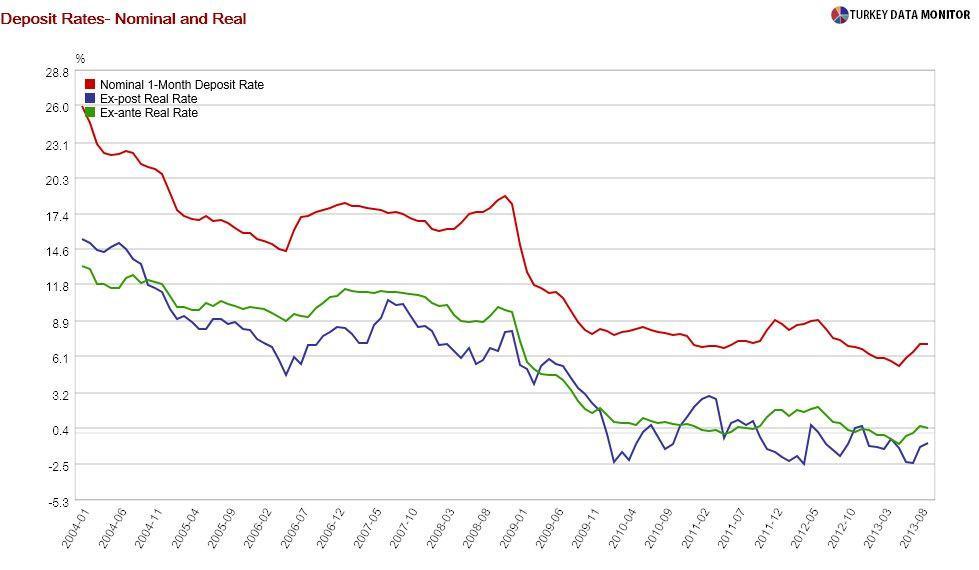

Therefore, one obvious way to tackle the deficit is to increase the country’s low private savings rate. However, this is more easily said than done. As I argued in earlier columns, there are structural reasons behind the plunge in private savings, such as the fall in women’s participation in the work force. But a nearly-zero real interest rate is not helping, either.

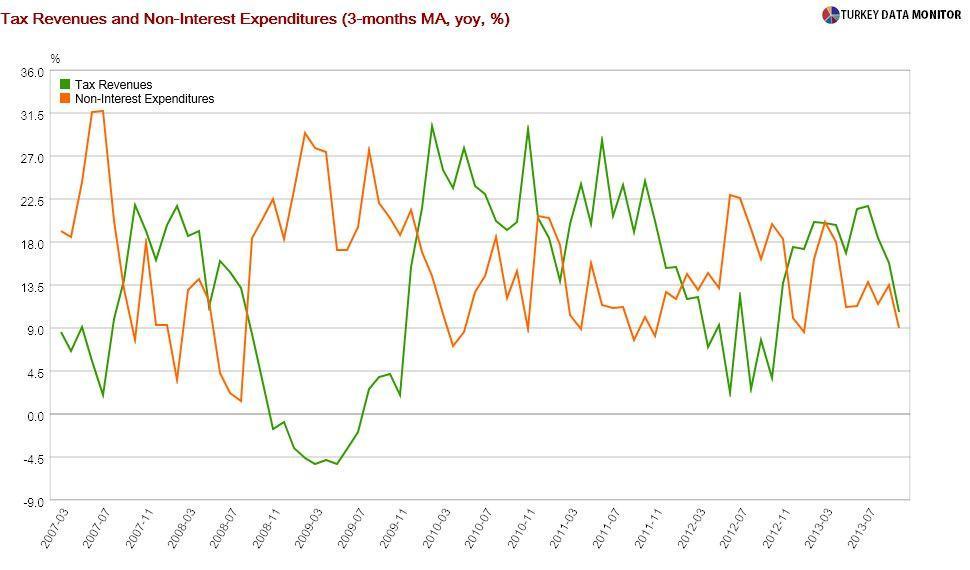

Another would be to run a tight fiscal ship, as the undersecretary of the Ministry of Finance correctly pointed out at the İzmir Economic Congress at the end of October. But his boss Mehmet “Nominal” Şimşek continues to hide behind the headline figures while ignoring that the rise in real expenditures has been concealed by the strong increase in tax revenues. Someone should tell him denial is not a river in Egypt.

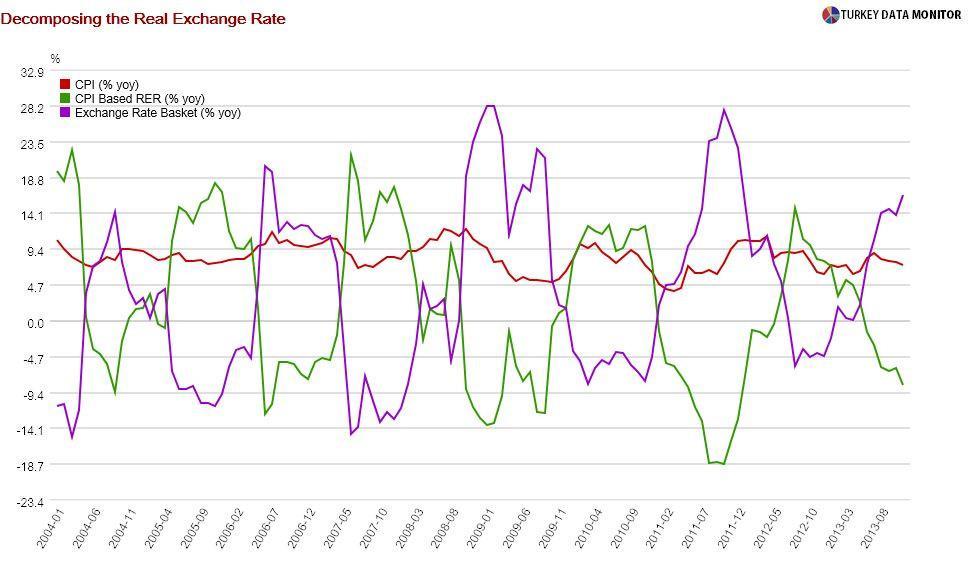

Yet another way would be to work directly on the current account deficit itself by promoting exports and reducing their reliance on imports. Although there is an obsession with the nominal exchange rate as the main cause of Turkey’s lack of competitiveness, inflation has traditionally been the deciding factor in the real exchange rate, which is the correct measure of competitiveness. Besides, a Central Bank survey of exporters in 2009 revealed that they prefer imported intermediate goods because there are no high-quality domestic alternatives.

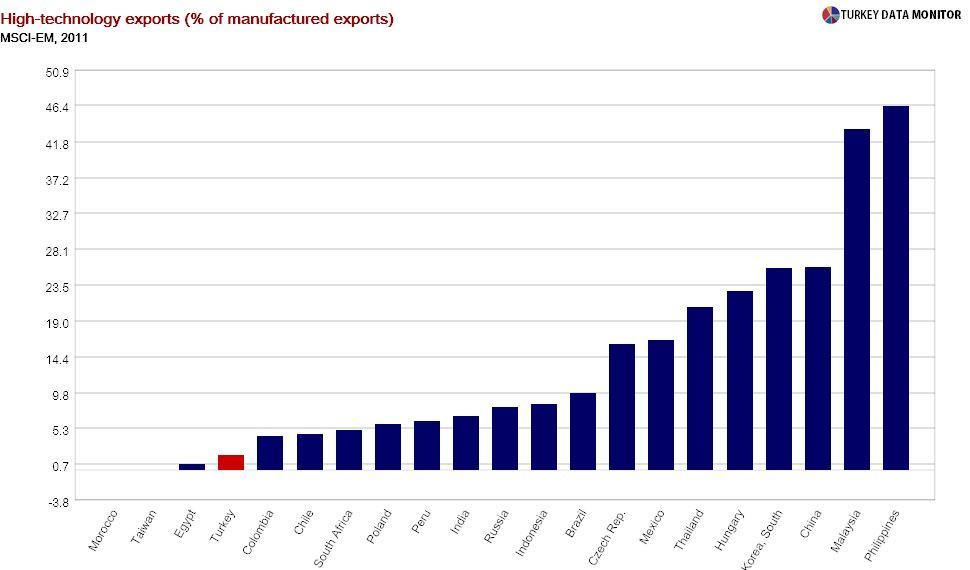

On a more basic level, not only does Turkey not export sophisticated, higher value-added products, but the country is not part of high-tech global supply chains, either. Why is that? Is it because of the country’s lack of innovation? Or is it because the environment is not very conducive to doing business? How about the faulty education system? Or the difficulty of getting products shipped quickly and cheaply?

But there is an inherent problem with this approach. Even if all the necessary remedies are implemented tonight, full benefits will not be reaped right away. While this is not an argument for not undertaking the necessary reforms, we have to find a way to live with the current account deficit in the meantime. That’s where I will pick up on Monday.