The ‘New Turkey’ and its discontents

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

‘The New Turkey and its Discontents’ by Simon A. Waldman and Emre Çalışkan (Hurst, £15, 344 pages)

Writing a primer on the situation in contemporary Turkey is a perilous task. Events pile on top of one another at such a pace that anything written is at risk of going out of date within days. That is especially true for book authors, as the entire landscape can shift in the months between submission and publishing.

The authors of “The New Turkey and its Discontents” fired off their final draft just days before last July’s coup attempt. Simon Waldman of Kings College London and Emre Çalışkan of Oxford University were able to make some adjustments to the text to address the failed military takeover, but actually they need not have panicked. The aftermath of the coup attempt has really only accelerated authoritarian trends that were already well in motion.

The authors of “The New Turkey and its Discontents” fired off their final draft just days before last July’s coup attempt. Simon Waldman of Kings College London and Emre Çalışkan of Oxford University were able to make some adjustments to the text to address the failed military takeover, but actually they need not have panicked. The aftermath of the coup attempt has really only accelerated authoritarian trends that were already well in motion.

The book is a judicious general overview on how Turkey got to where it is today. At little over 200 pages plus endnotes, some parts are necessarily short on detail, but overall the book charts the grim course of how Turkey went from a rising emerging market poster boy to standard bearer of today’s new “illiberal democracy.”

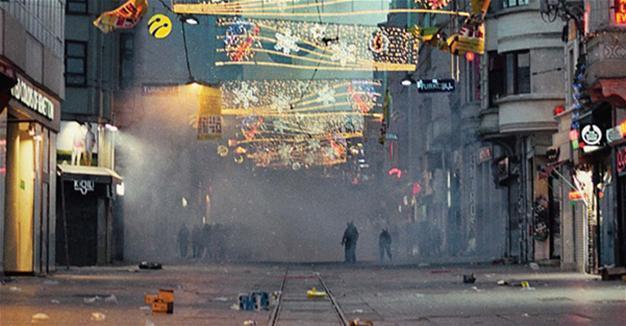

At the center of the volume is an exploration of the demise of the Turkish military as a political force, which the authors describe as “perhaps the most important development since the founding of the Turkish Republic in 1923.” Last year’s failed coup was in many ways an anomaly – a minority uprising by a small and ill-disciplined group within the Armed Forces. Bloody and destructive as it was, the putsch’s failure was symptomatic of the military’s fragmentation and decline.

Particularly since the coup of 1980, Turkey’s political climate had been subject to the overweening presence of the military prior to the Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) ascension to office. As Waldman and Çalışkan write, “Not only did the military set the rules of civilian politics, the constitution was drafted and implemented under its auspices. Through bodies like the National Security Council, the military’s presence served as a check on government power, but by no means a democratic one, and in a system controlled by the military itself, with a weak separation of powers.”

The book describes how the EU reform process pursued by the AKP was crucial to the sidelining of Turkey’s politicized military in the early 2000s. By the time of the trumped up anti-military Ergenekon and Balyoz investigations after 2008, the armed forces’ power had already critically declined as a result of the EU reforms and the failure to suppress the AKP through the courts.

There were hopes that the decline of the military would help solve Turkey’s decades-long Kurdish question, but that remains as militarized in parts of southeast Anatolia today as it was in the dark days of the 1990s. The removal of the military from the political scene also threw up other questions. “After the era of military tutelage, Turkey’s political structure was ripe for dominance by a single political party and a single political figure,” the authors write. This process has resulted in “the erosion of the checks and balances needed in any healthy democracy, in a political system that was already problematic and highly centralised.”

In drawing a deeper background to this picture, the book traces the various trends within strands of nationalist conservatism from the 1950s to the 1980 military coup and beyond, placing today’s AKP within this ecosystem. It is particularly deft on the “Turkish-Islamic Synthesis,” pursued by the military authorities after 1980 in an attempt to unite the violently divided country under a conservative nationalist tent. This project “was neither about religiosity nor political Islam. Rather, it was a cultural phenomenon that emphasized not piety but the centrality of Islam to Turkish identity and history,” the authors write.

But it is easy to see how the Turkish-Islamic Synthesis could bleed into political Islam, which rose steadily throughout the 1980s and 90s. One Islamist precursor to today’s AKP, Necmettin Erbakan’s Welfare Party, came to office in a coalition government in 1996, and this proved a step too far for the military, which overthrew it in a “post-modern coup” in 1997. But this was too late, Waldman and Çalışkan write, as “in sponsoring the Turkish-Islamic Synthesis, the military had let the proverbial cat out of the bag.”

The followers of Islamic preacher Fethullah Gülen were among the many religious groups that flourished after 1980. Once close allies of Erdoğan and the AKP government, the Gülenists have done more than most to contribute to today’s bitter atmosphere in Turkey through its campaign of dirty tricks and misdeeds. Waldman and Çalışkan are not blind to Gülenist transgressions, but the book perhaps does not weigh those transgressions heavily enough.

Today the government and others accuse the Gülenists of being behind last year’s coup attempt. “The fact that the president and the ruling party are former bedfellows of a movement that they themselves accuse of attempting a military takeover calls into question the competency of elected government officials,” Waldman and Çalışkan argue carefully. “If the Gülen movement was indeed behind the putsch, then surely it would be a scandal that the AKP … had allowed this dangerous and nefarious group to embed itself within state apparatus.” They are also right to say the true victim of the attempted coup was not the government, but rather the Turkish public: “Public officials owe them a detailed explanation, which has not yet been forthcoming.”

Since the coup attempt the government and President Erdoğan have reached unprecedented levels of popularity and unprecedented levels of power. So far over 135,000 people have been fired or suspended from the state, exacerbating security weaknesses at a time when Turkey is vulnerable to ramped up attacks by ISIS jihadists and PKK militants.

As for the future, Waldman and Çalışkan say “Turkey desperately needs to fix its political climate,” “strengthen its democratic institutions and governance,” and “reinforce its fragile system of checks and balances with a clear separation of powers.” All of this is certainly inarguable, but given the current bitter climate they seem rather forlorn suggestions. Still, as a diagnoses of how Turkey got to where it is today, “The New Turkey and its Discontents” is the probably best volume in English out there.

* Follow the Turkey Book Talk podcast via Twitter, iTunes, Stitcher, Podbean, Acast, or Facebook.