The Boys are Dead: The Roboski massacre and Turkey's Kurdish question

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

A man leaves his home during a curfew in the restive Sur district of Diyarbakır on Feb. 3, as Turkish security forces continue operations against urban-based PKK-linked militants. AFP Photo

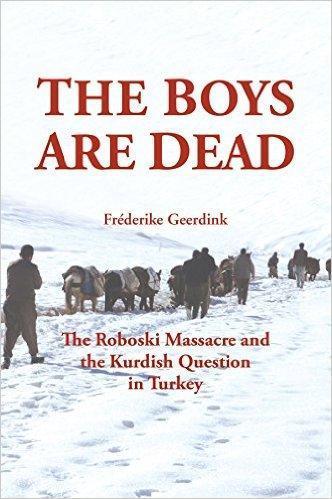

‘The Boys are Dead: The Roboski Massacre and the Kurdish Question in Turkey’ by Frederike Geerdink (Gomidas Institute, $22, 196 pages)On the evening of Dec. 28, 2011, 34 villagers were killed in an air raid in Uludere near the Turkey-Iraq border. Mostly children, the Kurdish villagers of Turkish nationality were returning with loaded mules from a regular cross-border smuggling trip when the Turkish Air Force jets struck, leaving all but four of them dead.

The bombing is at the center of this book by Dutch journalist Frederike Geerdink. Based in Istanbul from 2006, shortly after the attack Geerdink moved to the southeastern city of Diyarbakır, where she focused more closely on Kurdish matters. Digging deeper, she made countless trips to Uludere (“Roboski” in Kurdish) trying to shed light on the incident, staying for extended periods with families of the victims. “The Boys are Dead” describes the tragic history and present of Turkey’s Kurdish issue through the Uludere bombing, which Geerdink says “encapsulates the Kurdish question in a single square kilometer.”

The bombing is at the center of this book by Dutch journalist Frederike Geerdink. Based in Istanbul from 2006, shortly after the attack Geerdink moved to the southeastern city of Diyarbakır, where she focused more closely on Kurdish matters. Digging deeper, she made countless trips to Uludere (“Roboski” in Kurdish) trying to shed light on the incident, staying for extended periods with families of the victims. “The Boys are Dead” describes the tragic history and present of Turkey’s Kurdish issue through the Uludere bombing, which Geerdink says “encapsulates the Kurdish question in a single square kilometer.”Geerdink reported from southeast Anatolia for the international media until she was deported by Turkey after a trial in September 2015. The authorities accused her of aiding the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and violating a security zone in the Hakkari province, but in truth she had long been annoying them and the decision to deport her didn’t come as a big surprise. Critics always accused her of pro-PKK partiality; they are unlikely to change their mind after reading this book.

But she is certainly more courageous than many of her critics. Hugely intrepid, she traveled around the region, staying with and listening to locals caught up in the conflict, negotiating checkpoints, and braving relentless attacks by bedbugs. Probing the Uludere bombing from the site itself, she uncovered far more than the official parliamentary inquiry, which she shows was little more than a government stitch-up.

With conflict again raging in towns across the southeast after the collapse of a two-year ceasefire last summer, real journalism by eyes on the ground is more valuable than ever. Some have visited the region in recent months, but Geerdink’s deportation and the arrest of VICE News fixer Mohammed Rasool seem to have dissuaded many foreign journalists in Turkey from taking the risk. The less said about mainstream Turkish media coverage the better.

But this book is still far from perfect. You don’t have to be a believer in the sacred (and probably unattainable) journalistic value of “objectivity” to find some of Geerdink’s work quite unbalanced. Her account of the early years of the PKK, during which it brutally eliminated its rivals and all who stood in its way, is very soft. “In the early years,” she admits reluctantly, “the PKK targeted rival Kurdish revolutionary groups and rich Kurdish landowners. Öcalan and his followers used weapons and violence against them.” At times she veers into apologia or even justification. “It’s true that the organization has killed civilians, including Kurds, but never like [Uludere], and most of these murders took place in the early years of the PKK … between the 1970s and 90s,” she writes. “The victims were usually village guards, feudal leaders, members of families or clans opposed to the PKK, or else PKK members who had turned against the movement, criticized the organization or its leaders or were suspected of doing so.” This is hand-wringing.

In an asymmetrical conflict it may be more pressing for journalists to hold the state to account, but a book investigating the Kurdish movement shouldn’t take PKK wrongdoing so lightly. The charge sheet is long: From extortion to pressure on local businesses to observe shutdowns, from the torching of schools to the recruitment of child fighters, and the dangerous cult of personality around jailed PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan. Recognizing these things may play into the hands of destructive Turkish nationalism, but ignoring won’t make them go away. Geerdink is genuinely concerned not to be seen as partial, but you have to question a description of the PKK as “an organization based on communist ideals that fights the Kemalist state system as well as exploitation by the ruling class.”

The book is far from being PKK propaganda, but there’s an implied assumption throughout that the Kurdish political movement speaks for all Kurds. It’s true that Geerdink’s work focuses mainly on the PKK and the motivations of its sympathizers, but there are few ambivalent voices over almost 200 pages. It would be worrying if everything were so black and white that there were no PKK skeptics across the entire southeast, but there certainly are (Kurds from Turkey, for example, account for hundreds of recruits joining ISIS across the border).

Nevertheless by focusing on the Uludere massacre Geerdink highlights an essential point: Justice (and the lack of it) is absolutely central to the Kurdish issue. Particularly during the 1980s and 90s the conflict was marked by extra-judicial killings, mass unmarked graves, rampant torture, and forced displacement of over a million people. A truth and reconciliation mechanism for all this has been demanded by the Kurdish side, but it was never on the agenda of the government and was completely missing from public debate during the now-collapsed peace process.

There are plenty of theories about why the peace process broke down and neither side is blameless. But the issue is now not only about cultural rights and political demands; Ankara’s utter unwillingness to engage in a sincere historical reckoning helped reignite the fuse of the Kurdish insurgency. All too often President Erdoğan and the AKP have taken the easy route, cleaving to their nationalist-conservative base, lacking the courage to take bold, necessary, unpopular steps. This only emboldened the most uncompromising voices on either side.

Geerdink’s book highlights how injustice remains an open wound across the Kurdish southeast. The questions raised by “The Boys are Dead” should be at the front of everyone’s mind as clashes between Kurdish militants and the Turkish security forces continue to rage in curfew-stricken towns.

*An interview with Frederike Geerdink will be posted on the Turkey Book Talk podcast on Feb. 5. Listen or subscribe via iTunes here, Soundcloud here, or Podbean here.