The black eunuchs of the Ottoman Empire

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

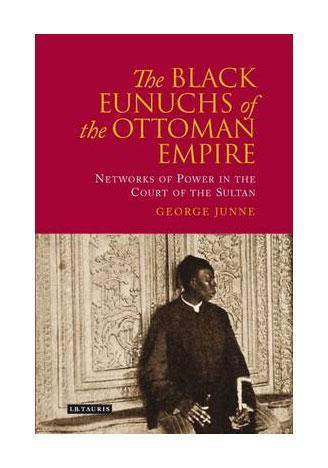

A eunuch of the Ottoman sultan. Photograph by Pascal Sebah, 1870s.

‘The Black Eunuchs of the Ottoman Empire: Networks of Power in the Court of the Sultan’ by George Junne (I.B. Tauris, 336 pages, £64)There are few more exotic subjects than the eunuchs of the Ottoman Empire. But despite being key centers of power for over three centuries, Ottoman court eunuchs remain something of an enigma. “The Black Eunuchs of the Ottoman Empire” by University of Northern Colorado professor George Junne is pioneering work that casts light on a fascinating but shady subject. It includes plenty of stomach-churning descriptions of the castration process, but also addresses broader issues of slavery, Ottoman power dynamics and cultural inheritance. Reading about this strange world of black and white eunuchs, court mutes, dwarf eunuchs, and dwarf concubine mutes is also a good reminder of what a bizarrely different world it was at the heart of Istanbul until just 100 years ago.

Eunuchs had been present in earlier Islamic households and courts, but the Ottomans only adopted their use after conquering the Christian Byzantine Empire. Eunuch-making was one of the many Byzantine customs maintained after the 1453 Ottoman conquest of Istanbul. The seclusion of women in the harem was similarly adapted by Ottoman Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror from the practice of the Byzantine “gynaccea” (separate women’s apartments).

Eunuchs had been present in earlier Islamic households and courts, but the Ottomans only adopted their use after conquering the Christian Byzantine Empire. Eunuch-making was one of the many Byzantine customs maintained after the 1453 Ottoman conquest of Istanbul. The seclusion of women in the harem was similarly adapted by Ottoman Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror from the practice of the Byzantine “gynaccea” (separate women’s apartments). In the Ottoman court and other wealthy households, eunuchs served as neutral, unthreatening, non-gendered emissaries in a moral universe that was highly charged with sexual tension. There was plenty of demand for eunuchs, and a steady supply was guaranteed by Arab horsemen raiding Africa. Most died during the castration process, driving up the price of those who survived.

At their peak there may have been as many as 800 court eunuchs organized in a hierarchical, well-defined structure. The system was brutal, but there was a kind of meritocracy in place. “Eunuchs who served the sultan favorably, plus those who learned Turkish and who converted to Islam, could progress in the system. A few would procure appointment to administrative posts within the empire, some serving in Cairo and Medina,” Junne writes. There was a fascinating paradox: African eunuchs in the Ottoman Empire were slaves and could often be the objects of contempt and ridicule, but some could amass amazing power.

There were none more powerful than the Chief Black Eunuch (Kızlar Ağası). The Chief Black Eunuch carried out overt and covert missions for the sultan, and was the only officer permitted at all times to request an audience with the sultan. They had the authority to grant favors through which they could add to their riches (which reverted to the sultan after their death as they had no heirs). The Chief Black Eunuch also often helped with state appointments, served as a supervisor of the holy places under Ottoman dominion, built and rebuilt mosques in Istanbul and elsewhere, administered the properties and estates of the sultan’s mother and children, helped train young members of the court, and was entrusted with the venerated “Sancak Şerif” (Sacred Standard) of the Prophet Muhammad.

But however exalted they became, all black eunuchs remained outsiders and strangers. In the words of Junne, “The Ottoman power structure incorporated the Black eunuchs but Ottoman society, as a whole, did not integrate them.” As the Ottomans tried to reform through the 19th century, and as slavery was abolished internationally, black eunuchs came to be seen as an anachronistic, even embarrassing relic of a corrupted old order. By the time the Republic of Turkey was established and the Ottoman court was abolished in 1923, the once-mighty court eunuchs no longer had any role.

One wonders if any of today’s Ottoman revivalists in Turkey fantasize about reviving the imperial tradition of black eunuchs. If you were feeling mischievous, you might even argue that the eunuch heritage has already been symbolically revived in present day Turkey’s court politics. President Erdoğan is cocooned by a narrowing circle of obsequious yes men. Eunuchs surround the throne, flattering the Great Leader, unwilling and unable to tell him unpleasant truths. Old habits certainly die hard.