Social media and new political turbulence

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

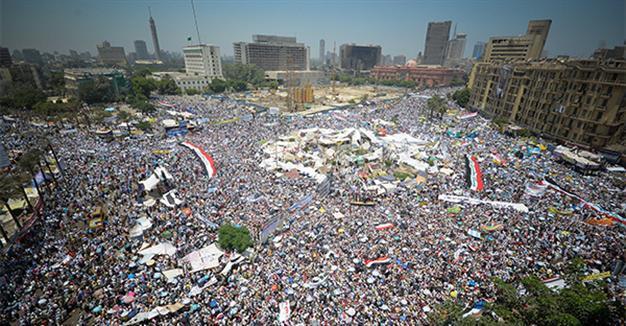

Tahrir Square in the Egyptian capital Cairo during protests against Hosni Mubarak in 2011.

‘Political Turbulence: How Social Media Shape Collective Action’ by Helen Margetts, Peter John, Scott Hale, & Taha Yasseri (Princeton University Press, $30, 304 pages)Turkey’s Gezi Park protests seem a long time ago. Back when they were still raging in the summer of 2013, parts of the western media were excitedly hailing them as the latest instance of global social media-driven anti-authoritarian unrest. Some optimistically hoped that social media would advance the cause of freedom everywhere, single-handedly helping people cast off regime-wrought chains.

The reality, of course, is murkier. Deeper academic studies of the effects of social media on politics have only recently started to appear, and have come to a range of conclusions. This book by four academics of the Internet at the University of Oxford and University College London gives an up-to-date account of current research on the subject. We are, the authors write, in the midst of a “transitional period” in the first two decades of the 21st century. There is a structural transformation ongoing in how political information flows. We are moving “from a world dominated by paper, broadcast media, and face-to-face communications, to a world where the Internet is the ubiquitous medium through which communication and coordination take place.” The near complete social mediation of information and opinion will have profound effects on political activity.

The reality, of course, is murkier. Deeper academic studies of the effects of social media on politics have only recently started to appear, and have come to a range of conclusions. This book by four academics of the Internet at the University of Oxford and University College London gives an up-to-date account of current research on the subject. We are, the authors write, in the midst of a “transitional period” in the first two decades of the 21st century. There is a structural transformation ongoing in how political information flows. We are moving “from a world dominated by paper, broadcast media, and face-to-face communications, to a world where the Internet is the ubiquitous medium through which communication and coordination take place.” The near complete social mediation of information and opinion will have profound effects on political activity.The book doesn’t come up with any particularly bold conclusions. In line with its title, it does suggest that the (inevitable) advance of Facebook, Twitter et al as the main platform on which people consume media is leading to increasingly turbulent politics, “characterized by rapidly shifting flows of attention and activity … unstable, unpredictable, and often unsustainable.” Mobilizations spurred by social media, the authors suggest, will “inject turbulence into every area of politics, acting as an unruly, unpredictable influence on political life.”

The focus of the book is on the Internet’s effect on political action, but I think its effect on the psychology of ordinary voters and how they conceive of politics will prove even more seismic. The late U.S. senator Daniel Moynihan once said: “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not to his own facts.” On social media that is no longer true. Facebook memes and the like have created new openings for extreme and simplistic ideas to gain traction with the broader public. Widespread disinformation is contributing to profound cynicism and apathy. There is certainly much to criticize about traditional media, but its sidelining as information “gatekeeper” is also leading to less wholesome and also less predictable consequences. Optimists herald the way social media isn’t bound by the compromises of the mainstream media, but its growth has thrown up a whole new set of questions.

Some hoped that Twitter would usher in a new public sphere based on dialogue, mutual respect and engagement across ideological lines. The opposite seems to have occurred. Social media platforms encourage aggressive discourse and obliterate ambivalence. Emotions are forced into binary oppositions: You “like” something or you don’t. The volume of debate is increased, not the quality. Once promised as empowering, social media may in fact merely entrench people’s views. Adversaries are encouraged to retreat to their respective ideological camps, reinforcing each other’s prejudices. Like-minded, self-selected communities cultivate shared narratives, identities and arguments in unchallenging echo chambers. The result is a steady siloization of political discourse, where the most basic facts – or even agreement on which facts are important as a starting point – is impossible. Some say Mark Zuckerberg should pay compensation for all the damage he has done.

Of course, grumbling about the polarizing effects of social media is nothing new. Perhaps it’s misguided. The authors of “Political Turbulence” say there is no evidence to support the idea that the echo chamber effect happens any more online than offline. Instead, what reigns is “chaotic pluralism”: A “time-based world stream ... pumping out and receiving information and social influence, in which [people] are exposed to many contradictory and overlapping currents of information, views, influences, causes, campaigns, and concerns that widen rather than narrow their experience.” They will not respond to this cacophony in a predictable or consistent way, and the political world will only become more diverse and fragmented.

I’m skeptical about this. My sense is that people are actually reacting to chaotic pluralism not by engaging randomly, but by retreating into comforting, rigid narratives that align with their pre-existing interests and concerns. Anecdotal experience in Turkey suggests that social media, (which, it must be said, fills an important space where the craven mainstream media dare not step), is exacerbating division into antagonistic camps. Polarization can happen with or without the Internet, but it’s too optimistic to declare that social media isn’t making it worse. The authors are right that social media is making politics more turbulent, but the effects of this turbulence still aren’t clear.