‘Queering Sexualities in Turkey’ by Cenk Özbay

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

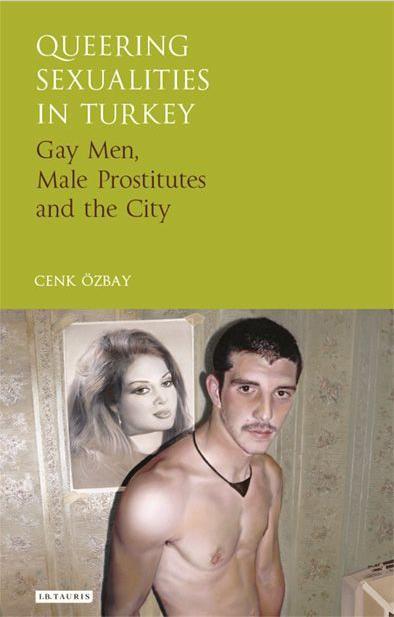

‘Queering Sexualities in Turkey: Gay Men, Male Prostitutes and the City’ by Cenk Özbay (IB Tauris, 194 pages, £64)

‘Queering Sexualities in Turkey: Gay Men, Male Prostitutes and the City’ by Cenk Özbay (IB Tauris, 194 pages, £64)Since 2014, controversy has erupted every summer around the LGBT Pride March in Istanbul. The event had taken place at the end of June without incident for 13 years running, but for the past three years it has been banned by the authorities citing security concerns and public morals.

From an almost standing start, LGBT rights campaigners in Turkey have built up impressive momentum. But no good deed goes unpunished; the movement’s increased visibility has led to an inevitable backlash from the conservative majority. The annual police crackdown on the Pride March is the clearest example of the general darkening atmosphere. From being an unwelcome but essentially harmless curiosity, LGBT rights campaigners are now often characterized as a nefarious Western imposition aiming to destroy the unity of the nation.

From an almost standing start, LGBT rights campaigners in Turkey have built up impressive momentum. But no good deed goes unpunished; the movement’s increased visibility has led to an inevitable backlash from the conservative majority. The annual police crackdown on the Pride March is the clearest example of the general darkening atmosphere. From being an unwelcome but essentially harmless curiosity, LGBT rights campaigners are now often characterized as a nefarious Western imposition aiming to destroy the unity of the nation. Sabancı University Associate Professor Cenk Özbay’s “Queering Sexualities in Turkey” was researched and written in the early 2000s, largely before LGBT issues became part of public consciousness. Its subject has also changed significantly in the years since: The largely analogue world of gay bars and hangouts that Özbay describes has almost entirely migrated to smart phones apps. But the book remains a fascinating window into the interaction between class and sexuality.

Özbay’s research focused on the little-known underworld of male sex work in Istanbul. He interviewed dozens of subjects to draw a panorama of this landscape. The subject, he suggests, brings assumptions about gay behavior, masculinity, and class values into sharp focus. Neither transactional male sex nor homosexuality are criminalized in Turkey, but neither are normalized.

Transactional male sex work is a “rigidly classed sexual economy,” he writes. Class is, Özbay suggests, “almost always the single most significant determinant in any story I have heard.” Rent boys generally come from the poor urban periphery, “varoş” in popular Turkish parlance. Their customers, meanwhile, are generally middle aged, with upper-middle class tastes and social capital. “When gay men and rent boys meet … it is an encounter between two classes and social positions, sexualities, bodies and manners and two gravely different symbolic worlds which normally wouldn’t bump into each other,” writes Özbay.

This encounter involves a host of assumptions about masculinity. Sellers of sex tend to embody an exaggerated heterosexuality. In Turkey the term “varoş” is generally used in a derogatory sense, but in gay slang it also “highlights robust virility and an authentic, uncontaminated masculinity,” writes Özbay. The “exaggerated masculinity” of rent boys looking for customers is thus often strategic: “They tactically constitute their identities as varoş to underline their differences from their gay clients … Rent boys repeatedly state that they are ‘real’ men because they are coming from varoş. In this way, the varoş is naturalized and linked to an inherent masculinity that gay men do not (and cannot) have.”

Because they almost always take the active “top” role in sexual intercourse, most of those selling sex do not even see themselves as engaging in a homosexual act. Many deny that they are sexually attracted to men, while others simply try to preserve a perceived masculine ideal, unable for class reasons to follow the codes of the middle-upper class gay lifestyle. “The position of rent boy subverts the absolute duality between homo- and heterosexuality,” Özbay writes. Ultimately, sexual affinities are generally far murkier than rigid popular imagination would suggest.

Class issues are also embroiled in complex questions of local and global culture. Özbay refers to “globalized, modern gayness, embellished with signs of transnational cultural capital.” This contrasts with the exaggerated masculinity of rent boys, loaded with assumptions about being locally rooted. The term “gay” thus takes on a different meaning, associated with a set of non-masculine, globalized, upper-middle class social codes.

“Queering Sexualities in Turkey” contains some fascinating insights. Unfortunately it often echoes some of the clumsy academic language popular in some of the humanities, which is sometimes used to cover up unoriginal thinking. In this book it simply makes it more difficult to focus on the many more interesting aspects of the work.

The landscape that Özbay’s describes may have radically shifted in the years since he conducted the research, but his book remains a very worthy read.

* Follow the Turkey Book Talk podcast via iTunes here, Stitcher here, Podbean here, or Facebook here, or Twitter here.