The Chapull-Jew (çapulcu) interest rate lobby

I thought the government had forgotten about them, but Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan brought up the mysterious interest rate lobby during his speech outside the airport upon his arrival from his North African Rainbow Tour.

I thought the government had forgotten about them, but Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan brought up the mysterious interest rate lobby during his speech outside the airport upon his arrival from his North African Rainbow Tour.“The interest rate lobby believes it can threaten Turkey with stock market speculation,” Erdoğan said. He did not specify who the members of this lobby were, so I had to resort to pro-government newspapers. According to articles in a daily owned by the conglomerate where the PM’s son-in-law is CEO, the lobby is a coalition of Jewish financiers associated with both Opus Dei and Illuminati. It seems the two sworn enemies have put aside their differences to ruin Turkey.

They are supported by the foreign media. Attacking a Bloomberg journalist in 2011, the same paper implied that Bloomberg, owned by a Jew, served the finance sector, also run by Jews. Such religious fraternity would be natural to the proponents of this theory, who are used to cozy relationships with the government and policymakers. It also takes for granted that the many investors holding Turkish assets can easily coordinate. Maybe, they are organizing through Twitter. No wonder the PM calls the social networking platform “a menace.”

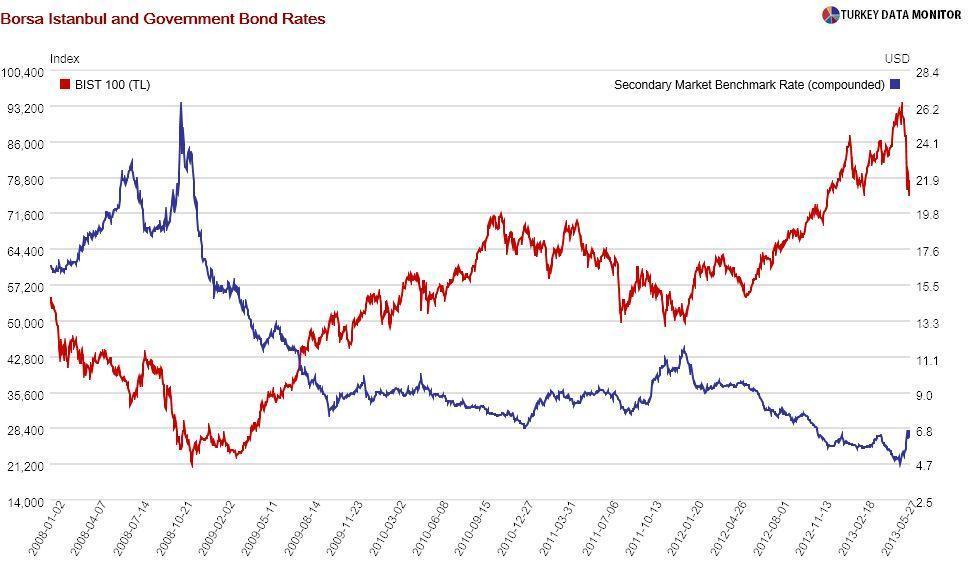

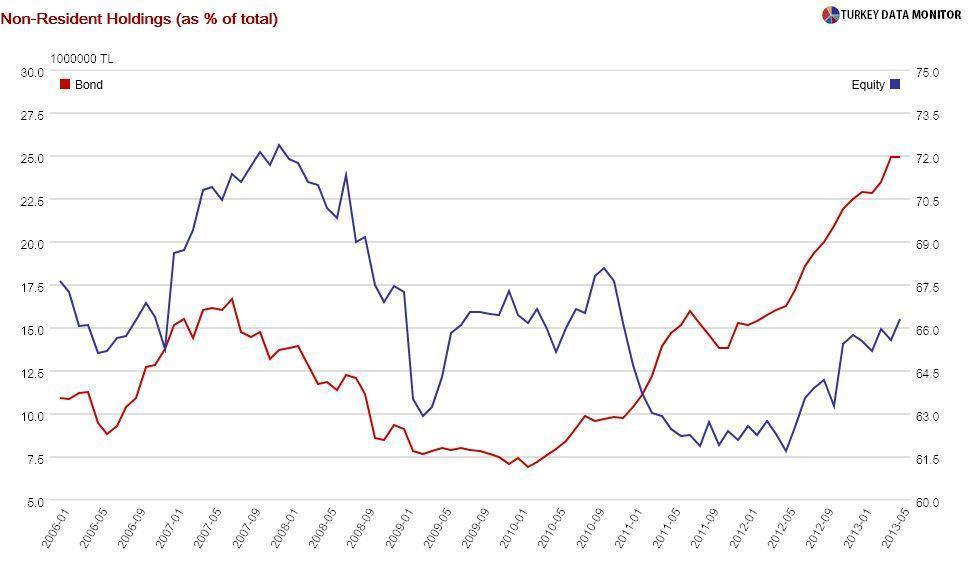

Even if they, at least the ones with the biggest exposure to Turkish assets, managed to come together for such a plot, their interests would not necessarily align. For example, anyone holding Turkish government bonds would be hurt by the rise in interest rates, which are inversely related to bond prices.

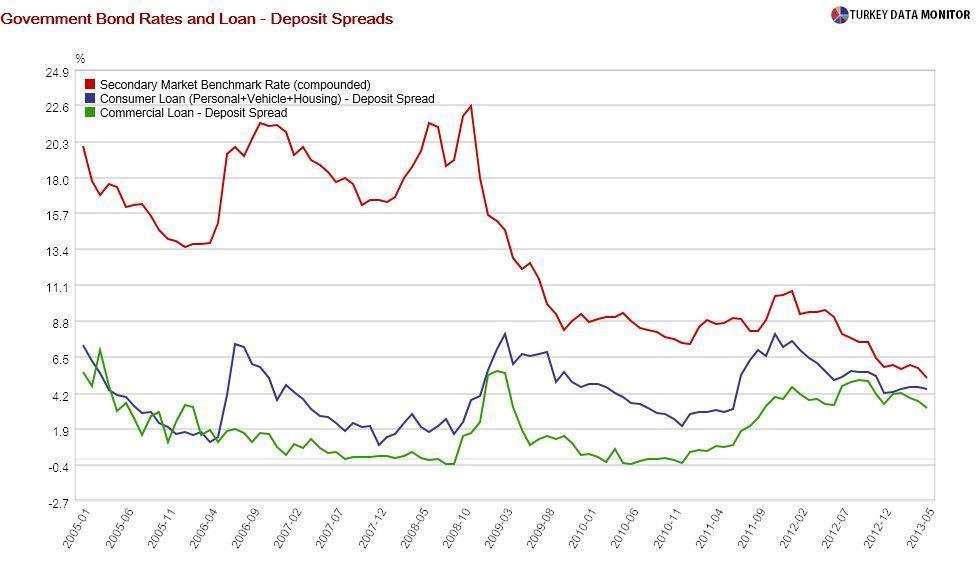

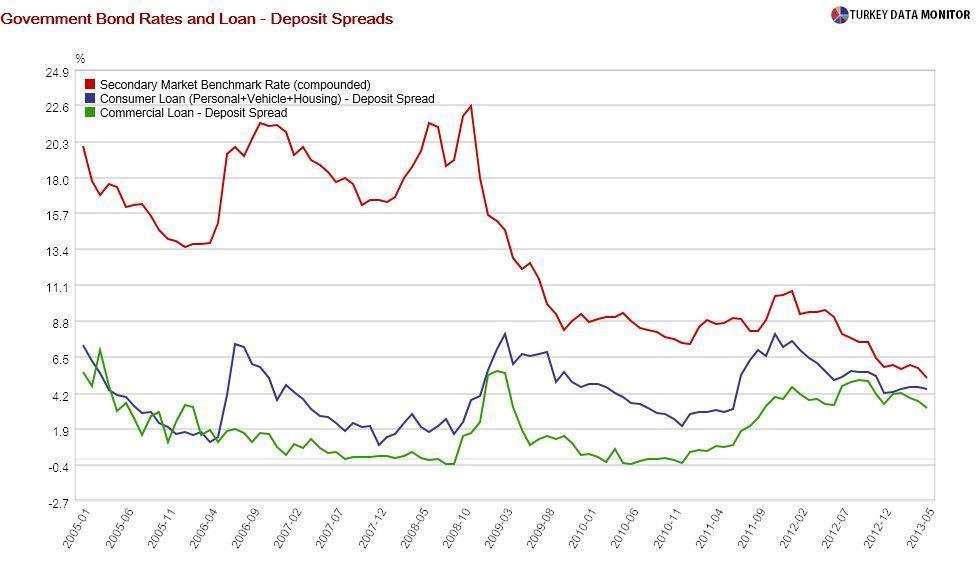

Higher yields are usually associated with worse equity performance. For one thing, Turkish banks hold quite a bit of government bonds. Besides, bond rates don’t have a meaningful relationship with the loan deposit spread. If anything, deposits have a much shorter maturity than loans, and so higher yields would aggravate this maturity mismatch. As for non-banks, higher rates mean higher borrowing costs for them. Turkish equities indeed move in the opposite direction of bond yields.

Rising rates are hurting foreign investors who own nearly two-thirds of Turkey’s stock market. Only those who are shorting Turkey or bottom-fishing would benefit. And if there is an interest rate lobby, it is probably run by none other than Erdoğan. Last Monday’s bloodbath in Turkish markets was a response to the weekend’s police crackdown on peaceful demonstrators who he called "looters" (çapulcu, read as chapull-Jew). Equities plunged and the lira depreciated on Thursday when he repeated his hard-line stance.

Erdoğan also seems to have forgotten that he owes his fortunes to the very foreign investors he is attacking now. Without the investor confidence and accompanying capital flows, Turkey would not have achieved remarkable growth rates and received investment-grade from the rating agencies.

He wasn’t accusing them then. On the contrary, he was boasting of the benchmark government bond rate below 5 percent a couple of weeks before the demonstrations began.