‘Little Black Fish’ documentary lends a voice to children of war

Emrah Güler - ANKARA

The labeling of the collective attempts in the last half-a-decade on many fronts to bring Kurds more freedoms and rights, to bring an end to the war in the southeastern Turkey that has left its mark in the area for the last three decades and to help ending some deeply-rooted separatist notions has been called the Kurdish Initiative (or the Kurdish Opening), and later the Peace Process.

The labeling of the collective attempts in the last half-a-decade on many fronts to bring Kurds more freedoms and rights, to bring an end to the war in the southeastern Turkey that has left its mark in the area for the last three decades and to help ending some deeply-rooted separatist notions has been called the Kurdish Initiative (or the Kurdish Opening), and later the Peace Process. The process, at least, which has been a taboo subject only in the last decade, has reverberated on screens in the recent history of mainstream Turkish cinema. There has also been an emergence of an independent cinema by Kurdish filmmakers with distinctive voices, and to that end, some of the most powerful documentaries on the region’s recent history.

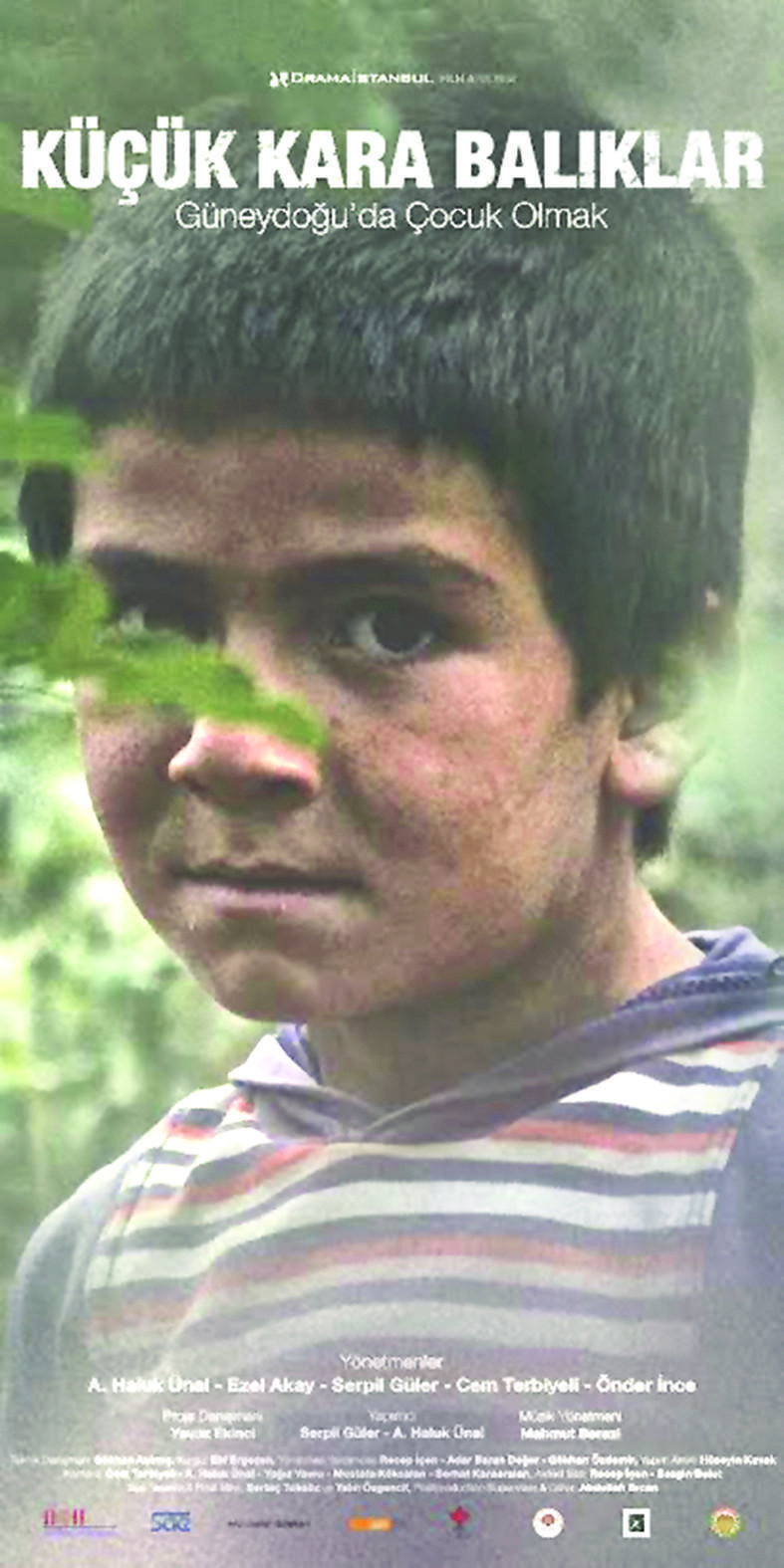

The process, at least, which has been a taboo subject only in the last decade, has reverberated on screens in the recent history of mainstream Turkish cinema. There has also been an emergence of an independent cinema by Kurdish filmmakers with distinctive voices, and to that end, some of the most powerful documentaries on the region’s recent history.One of the recent examples is a documentary produced by Drama İstanbul, a group specializing in script development, film project design and production, called “Küçük Kara Balıklar: Güneydoğu’da Çocuk Olmak” (Little Black Fish: Being Children in the Southeast). The film is a collective effort, directed by five filmmakers, A. Haluk Ünal, Cem Terbiyeli, Ezel Akay, Önder İnce and Serpil Güler, and is now available online at vimeo.com/108880966 for screening with English subtitles.

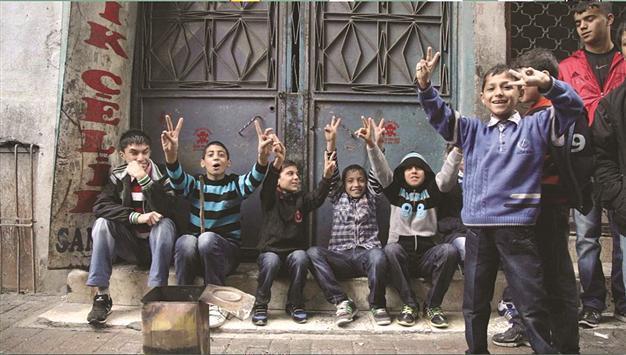

“Küçük Kara Balıklar” lends its narrative to first-hand accounts of 11 people who were children in the region in the heat of war, all who witnessed the horrors of war at different times. Some are in their thirties now, others are barely teenagers. With no narrator, and occasional footage of the mentioned events, the film takes its power from the accounts of real witnesses, told with sadness, confusion, anger, occasional humor and calm to make sense of the horrors they experienced as children.

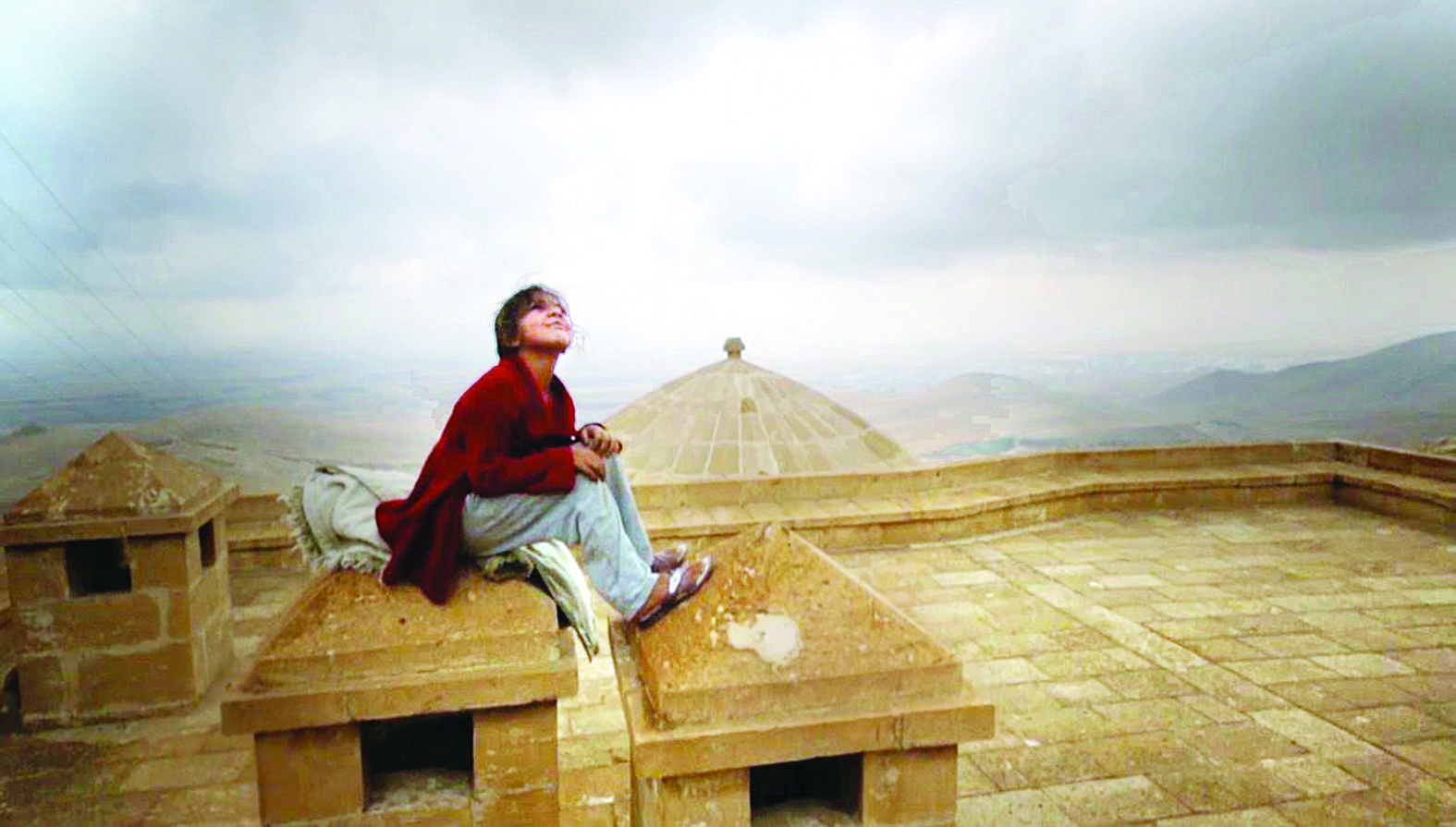

This is the story of children becoming adults overnight, children seeing their houses burn down, their fathers beaten, their mothers shot, their brothers running away to join the guerillas. This is the story of children seeing death for the first time. “Where in the hell are we, and why don’t the Turks care about us?” remembers one woman, asking as a child. “What do this nation’s people say?” That is, more or less, the gist of the film: children confused in the face of war.

Children becoming adults over night

One woman in her thirties talks about the stories, the “fairy tales,” they listened to when growing up: a woman leaving a little copy of the Quran for her two daughters and fleeing, the local creek turning crimson as observed by the women doing their laundry each day and finally turning the color of blood when the massacre nears the neighboring village. Another woman remembers her mother in a puddle of blood after being shot, how terrified she was and how that image of the blood became a monster eating her up. “We didn’t know what a monster was before then,” she said.

“In the 90s, no kids living in that region could say, ‘I lived well and fine,’” said one man, as he recalled his twelve-year-old brother being humiliated by the soldiers at a check point, and how the next day he left home, presumably to join the guerillas. “One night he suddenly grew to become more than 20 years old.”

They never heard of him again.

Children becoming adults is a recurring narrative among the witnesses. “As a child born in the southeast after the 90s, you are not really a kid,” sums up another woman in her twenties. “During your infancy, you’re really a child between one to five years old. As a six-year-old, you have actually grown up and are considered to be 15-years-old. When you turn 10, you’re actually 20. After 15, you feel like you’re 40 years old.”

None of the witnesses veer towards agitation or justified anger, telling their stories calmly and confidently. Some of them are in their thirties, others twenties and one little girl is eight years old, all of them clinging to life in their own devices. One man, who was severely wounded and lost one of his arms from a landmine when he was 12, channels his pain into running, competing in the 2012 Paralympics in London. Others take to music. Another young woman, having cried more than her fair share when she was a child, said, “There is always a smile on my face.”

None of the witnesses veer towards agitation or justified anger, telling their stories calmly and confidently. Some of them are in their thirties, others twenties and one little girl is eight years old, all of them clinging to life in their own devices. One man, who was severely wounded and lost one of his arms from a landmine when he was 12, channels his pain into running, competing in the 2012 Paralympics in London. Others take to music. Another young woman, having cried more than her fair share when she was a child, said, “There is always a smile on my face.”“As life takes from you, you start looking to take from life,” said another woman. “You are going to study and teach. You’re going to work. You’re going to make the effort so that life doesn’t see that you have been defeated.” Defeat has never been an option for these children of war. “In memory of all the school kids killed in the state-sponsored war zone,” is written as the ending titles roll. Then comes scrolling down the list of all the children who were the casualties of war, starting from 1988 and ending in 2014, ages one to 18, and we are reminded of the children who never made it to tell their stories.