Journey to the borderlands of Turkey, Greece and Bulgaria

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

Bulgarian border police patrol alongside a barbed wire fence on the Bulgaria-Turkey border, near the town of Lesovo. AFP photo

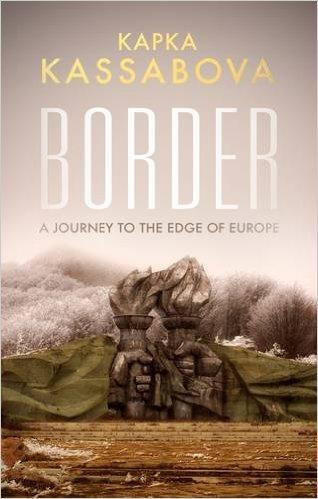

‘Border: A Journey to the Edge of Europe’ by Kapka Kassabova (Granta, 379 pages, £15)When Kapka Kassabova was growing up in Sofia, Bulgaria was on the frontline of the Cold War - the cut-off line between the Warsaw Pact countries of the Soviet bloc and NATO members Greece and Turkey. At the point where the Mediterranean and Balkan currents meet, the borderlands of Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey have for centuries been a place of migration, ethno-religious mixing and bloodshed.

“Border: A Journey to the Edge of Europe” mixes memoir, travelogue and history. Kassabova, a poet and travel writer who today lives in Scotland, visits “the forbidden places of my childhood, the once-militarized border villages and towns, rivers and forests that had been out of bounds for two generations.” She wonders what it takes “to dwell in a borderland so infused with ancient and modern myth.”

“Border: A Journey to the Edge of Europe” mixes memoir, travelogue and history. Kassabova, a poet and travel writer who today lives in Scotland, visits “the forbidden places of my childhood, the once-militarized border villages and towns, rivers and forests that had been out of bounds for two generations.” She wonders what it takes “to dwell in a borderland so infused with ancient and modern myth.” Kassabova travels around in an old Renault, uncovering surprising stories, sensitive to the many ironies in “the last outpost of Europe.” Back in the Cold War years, “the Turks were nervous about the Soviets and the Greeks, the Greeks were nervous about the Soviets and the Turks, and the Bulgarians were nervous about everyone,” she writes. “[It was] a military buffer zone for half a century ... the point where one ideology stopped and another began.”

The border was deadly. But it had a deceptively friendly reputation for being much easier to cross than the Berlin Wall. Thousands of fugitives headed to it from across Eastern Europe to escape from Bulgaria to Greece and Turkey. The topography of the border was falsified on GDR-made maps to confuse people, and hundreds were shot there over the course of the Cold War. Hundreds of others escaped.

In one haunting chapter, Kassabova writes about a forested area between Greece and Bulgaria full of trees bearing initials carved by people trying to flee. “When you tuned in, you could almost hear them whispering,” she writes. “The most heavily carved decades were the 1940s, the decade of war and starvation for Greece, and the 1990s, the decade of paupery and starvation for Bulgaria. In between were the deadly 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s of the Iron Curtain.” Such was a system “where the real enemy was not abroad, but inward.”

Of course, the region remains a crossroads today. It is a gateway for refugees heading in the other direction from Syria and Iraq, and there is now a huge “security wall” on the Bulgaria-Turkey border. “The corridors used in the Cold War remain the same. Only the direction of travel has changed,” writes Kassabova.

Expulsions and exodus have a long heritage in the Balkans. The Balkan Wars of 1912-13 saw the Ottoman Empire lose its last territories in Europe, prompting an exodus of Muslims from their ancestral homes. Muslims were forced out of Bulgaria, Macedonia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Albania and Serbia, with most ending up in Turkey. Millions of today’s Turkish citizens are their ancestors. A decade later, after the Turkish War of Independence, 1.5 million Greeks headed west, while 400,000 Greek Muslims headed the other way (and Greece simultaneously expelled half a million Bulgarian speakers). Centuries of coexistence were obliterated as hard, blood-soaked borders were thrown up.

The steady unravelling of complex ethnic tapestry has proceeded sporadically to today. Almost 100 years after the Balkan Wars, around 350,000 Turkish-origin Bulgarian citizens were effectively expelled from Bulgaria in summer 1989. This peacetime ethnic purge was based in an “asinine anachronism, invoking the ghost of ‘the Turkish yoke,’” Kassabova writes, “families, futures, and sometimes bodies were broken by their own state.” In a bitter irony, the expulsion took place just months before the Berlin Wall came down and the Cold War was suddenly over, making it “a last cretinous crime of twilight totalitarianism.” Perhaps the largest movement of people in Europe since World War II, it is today barely remembered outside Turkey. Kassabova manages to track down many survivors of this exile, who still have warm memories and maintain human contact with their old life across the border. They are, she writes, the last remaining “odd ragged bits of a once-rich human tapestry.”

A recurring theme in “Border” is that this is a land of deep-rooted ancient rituals. The few decades of communism was just a brief interruption. An “undercurrent of mysticism” remains stubborn. In the Strandja, the mountainous forested region of the Bulgarian-Turkish border, even Christianity is just “a fig leaf for a primal spiritual practice.”

A few decades of Soviet social engineering, Kassabova writes, “had made [people] scared and suspicious, but the land’s mysteries were still there. They spoke to those who could tune in.” She certainly can, and it makes for a splendid book.

* Follow the Turkey Book Talk podcast via Twitter, iTunes, Stitcher, Podbean, Acast, or Facebook.