If only Tayyip would say “Eureka! Europa Europa”

May 9 was Europe Day. May 9 is celebrated to commemorate French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman’s 1950 proposal to create a “supranational community” of European states. The Schuman Declaration formed the backbone of the European Union.

May 9 was Europe Day. May 9 is celebrated to commemorate French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman’s 1950 proposal to create a “supranational community” of European states. The Schuman Declaration formed the backbone of the European Union.

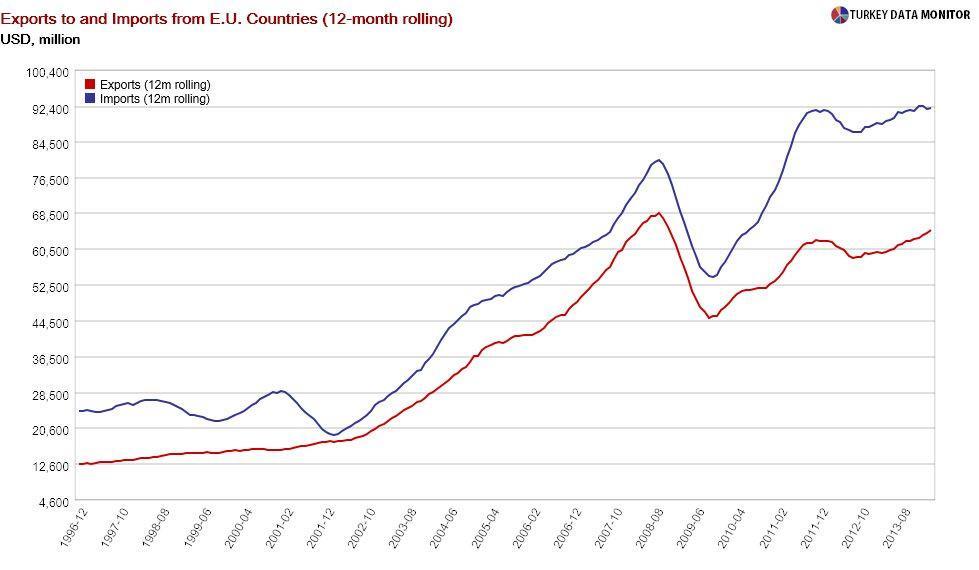

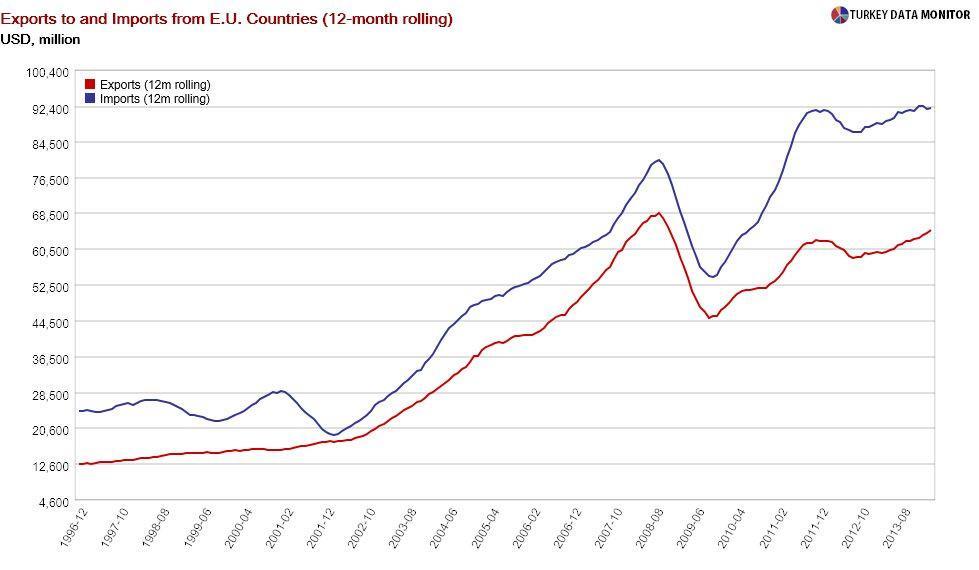

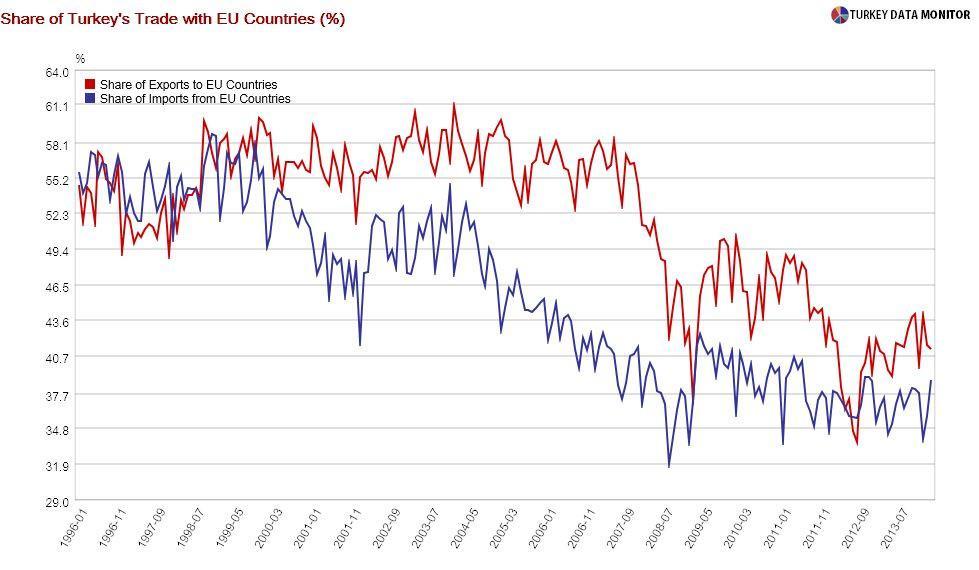

While EU membership is not even close, Turkey signed a Customs Union (CU) agreement with the EU in 1996. The value of bilateral trade between the two has increased more than fourfold since then, even though the share of the EU in Turkey’s total exports and imports has actually declined. The EU accounts for over three-quarters of foreign direct investment inflows into Turkey.

But the real benefits of the CU lie elsewhere. As in earlier research, a recent World Bank study found that the CU contributed to productivity gains among Turkish firms and “helped the alignment process with the EU’s acquis, improving the quality infrastructure and facilitating reform of technical regulations in Turkey to the benefit of Turkish consumers.”

The report recommends integration in agriculture and services as well, quantifying the potential benefits. It also addresses the CU’s unfair practices: Turkey is obliged to align with EU legislation but cannot participate in CU decision-making. Some EU free trade agreements have not been concluded with Turkey, resulting in one-way access to Turkish markets for third countries.

As much as it is important to move forward with the CU, I believe that Turkey’s EU negotiation process itself is even much more vital – even though actual membership is far away from the horizon, if at all possible. That is because it forces the negotiating governments to credibly promise to undertake important reforms they would otherwise be unwilling to embark on.

In economics, this is the concept of time inconsistency, which brought its founders, Finn Kydland and Edward Prescott, the Nobel Prize in 2004 – even though Odysseus had thought of the problem, and found a solution, more than 3,000 years before them. His tying himself to the mast, to make sure he would not be lured by the sirens, was a foolproof “commitment mechanism.”

In other words, the membership process provides an anchor, or a Homer-esque mast, for Turkey. At least, it did until Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan lost all interest in the EU and made someone who had no foreign affairs skills or experience whatsoever, the EU minister, probably because of his English-speaking and sycophantic skills.

There is an ongoing EU investigation into claims of tender-rigging and illegal recruitment at an agency linked to the EU Affairs Ministry under Egemen Bağış, one of the ministers who resigned during the graft scandal. His only impact on EU-Turkey relations was to declare, in an official declaration, that he personally wrote, with his impeccable English, that Turkey was not a banana republic.

It might as well be one with a prime minister who would prefer becoming president and continue to rule the land at his whim, rather than be constrained by the EU’s principles of democracy and rule of law.