How the Central Bank saved Erdoğan’s derrière

I couldn’t help but notice several misconceptions about Tuesday’s midnight’s emergency rate hike.

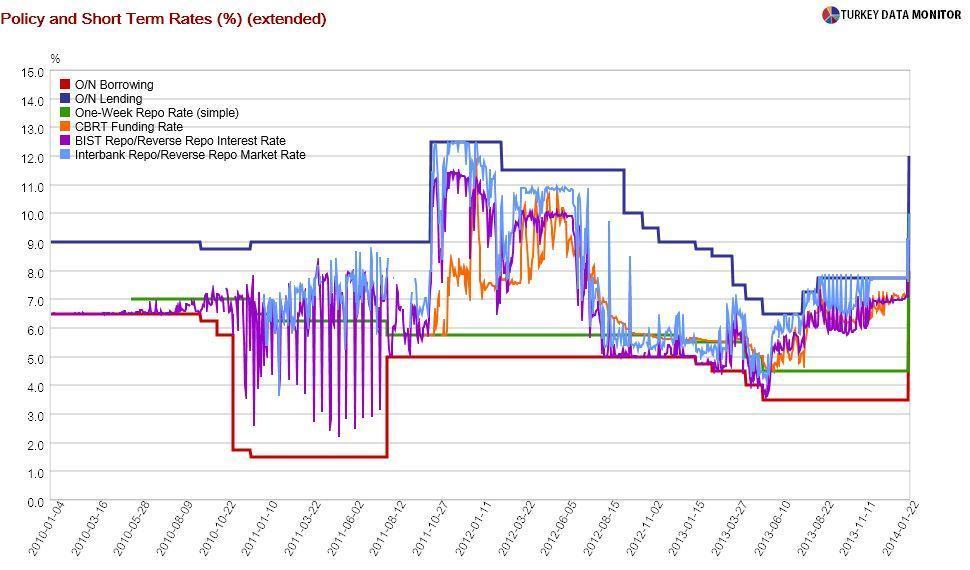

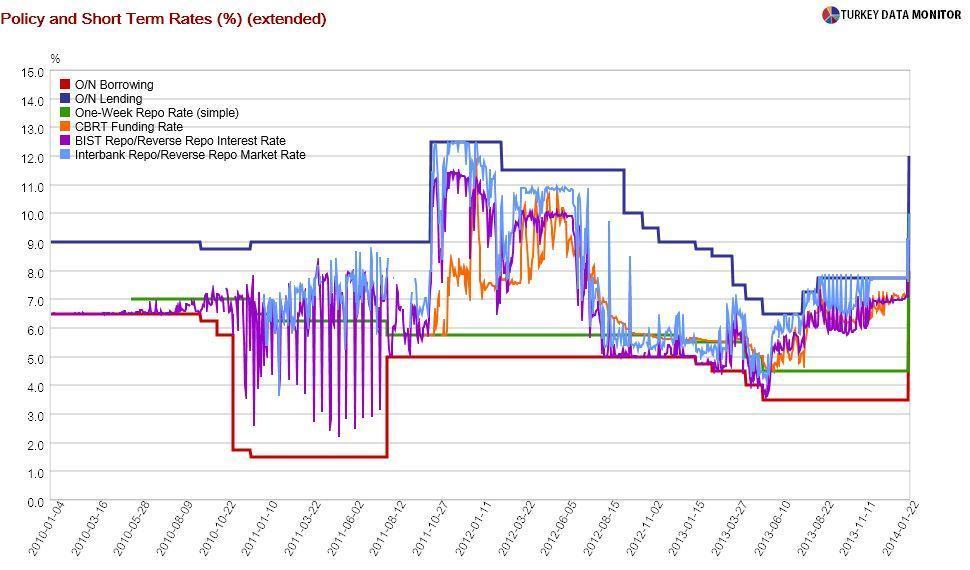

I couldn’t help but notice several misconceptions about Tuesday’s midnight’s emergency rate hike.First, the Central Bank did not hike rates 4-5 percentage points, as some claimed. It is true that they raised the marginal funding rate from 7.75 to 12 percent. But the Bank also said that liquidity would be provided primarily from the one-week repo rate instead of the marginal funding rate in the forthcoming period.

The Bank increased that rate from 4.5 to 10 percent. In a way then, its policy rate rose from 7.75 to 10 percent. Its average funding rate for banks, on the other hand, was 7.20 percent before the emergency meeting. That rate will eventually settle slightly above 10 percent. Similarly, the interbank repo rate, which was 7.75 percent before the meeting, will rise to 10 percent. So the effective rate hike is 3 percentage points at most.

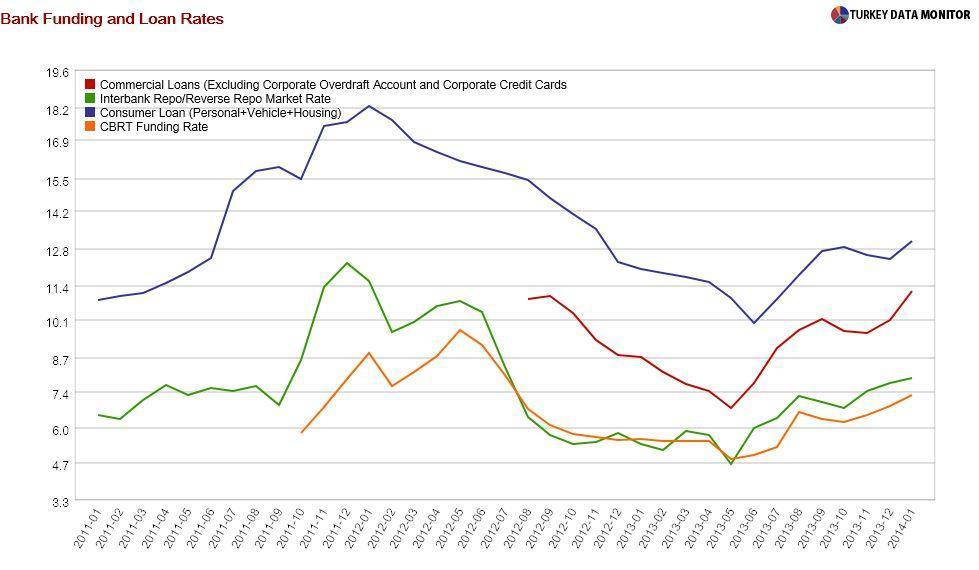

Some have also argued that the rate hike hurt the ruling Justice of Development Party’s (AKP’s) chances in the local elections, proving the Central Bank’s independence. Nothing could be further from the truth. While the rise in commercial banks’ funding costs will be reflected in higher loan rates, hurting businesses and consumers alike, it will take at least four or five months for the full effects of the hike to be felt on the economy.

The destruction in the corporate balance sheets and a probable currency crisis right before the elections would have hurt the AKP’s electoral chances much more. Make no mistake: Unlike Finance Minister Mehmet “Nominal” Şimşek’s claims, the effects of the hike on the economy will be severe, not least because it was applied to a slowing economy, where measures to curb consumption and credit were already in place. However, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan must be thinking there is plenty of time until the general elections to re-loosen monetary policy.

Therefore, I am not taking his warnings toward the Central Bank during his return flight from Iran too seriously. He just couldn’t congratulate the Bank from saving the country from a crisis (as well as his derrière) – not after all that talk on the interest rate lobby and his “elaborate” theories on how higher interest rates beget higher inflation.

Another misconception is the claim that the rate hike failed. Since the lira-dollar exchange rate was 2.30 before the rate decision and 2.26 24 hours later, one could argue that it could not stem depreciation. That reasoning ignores the counterfactual: Perhaps the exchange rate, which was 2.40 before the Bank announced the meeting, would have been above 2.50 today. The lira gave up some of the early gains the day after the hike when markets realized there would be no more additional monetary tightening. The negative emerging market sentiment played a role as well.

The latest rate decisions were also designed to make the policy framework simpler. But given the misconceptions about them, the problem could be with the receivers of information as much as the suppliers.