French cave home to earliest drawings wins World Heritage status

DOHA - Agence France-Presse

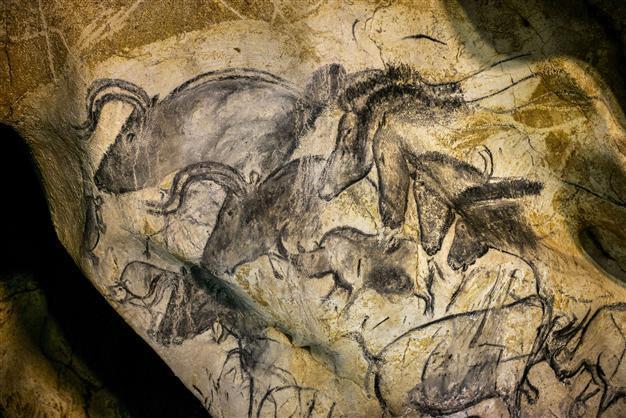

A view of paintings on the rock walls of the Chauvet cave, on June 13, 2014 in Vallon Pont d'Arc, southeastern France. AFP Photo

UN cultural agency UNESCO on Sunday granted its prized World Heritage status to a prehistoric cave in southern France containing the earliest known figurative drawings.Delegates at UNESCO's World Heritage Committee voted to grant the status to the Grotte Chauvet at a gathering in Doha, where they are considering cultural and natural wonders for inclusion on the UN list.

The cave in the Ardeche region, which survived sealed off for millennia before its discovery in 1994, contains more than 1,000 drawings dating back some 36,000 years to what is believed to be the first human culture in Europe.

"I had the chance, I should say the privilege, to visit the cave... and I was literally stunned by what I saw, which revolutionises our views of our origins," France's envoy to UNESCO Philippe Lalliot said after the vote.

A French lawmaker for the Ardeche, Pascal Terrasse, described the cave as "a first cultural act".

"This artist has now been recognised," Terrasse said. "May he forgive us for waiting 36,000 years to recognise his work."

UNESCO said the Grotte Chauvet "contains the earliest and best-preserved expressions of artistic creation of the Aurignacian people, which are also the earliest known figurative drawings in the world," UNESCO said.

"The large number of over 1,000 drawings covering over 8,500 square metres (90,000 square feet), as well as their high artistic and aesthetic quality, make Grotte Chauvet an exceptional testimony of prehistoric cave art."

The opening of the cave, located about 25 metres (yards) underground, was closed off by a rockfall 23,000 years ago.

It lay undisturbed until it was rediscovered by three French cave experts in 1994 and almost immediately declared a protected heritage site in France.

"Its state of preservation and authenticity is exceptional as a result of its concealment over 23 millennia," UNESCO said.

Access has since been severely restricted and fewer than 200 researchers a year are allowed to visit the cave, which stretches into several branches along about 800 metres and at its highest reaches 18 metres.

The painted images include representations of human hands and of dozens of animals, including mammoth, wild cats, rhinos, bison, bears and aurochs.

More discoveries are expected to be found in remote parts of the cave as yet unexplored.

The cave also includes remnants and prints of ancient animals, including those of large cave bears that are believed to have hibernated at the site.

Researchers believe the cave was never permanently inhabited by humans "but was instead of a sacred character" and "used for shamanist ritual practice".

With the cave itself closed to the public, authorities are building a full-scale replica of the site nearby, which is expected to open in the spring of 2015.

The Paris-based United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization oversees the system of granting coveted World Heritage Site status to important cultural and natural sites.

Obtaining the status for sites is a point of pride for many nations and can boost tourism, but it comes with strict conservation rules.

UNESCO delegates are meeting for 10 days in Doha to consider the inscription of 40 sites on the World Heritage List and issue warnings over already-listed locations that may be in danger.

Other sites given the status this year include a vast Inca road system spanning six countries and ancient terraces in the West Bank that are under threat from the Israeli separation barrier.