The June 2015 edition of popular history magazine “Derin Tarih” (Deep History)

claimed to expose the “hidden history” of how Freemasonry played a key role in bringing down the Ottoman Empire. The magazine is published by the same company that owns pro-Justice and Development Party (AKP) newspaper Yeni Şafak, and it is always full of similarly bombastic stories, revealing “historical documents” of dubious veracity. Freemasons may not be the AKP’s number one enemy, but residual paranoia about Freemasonry still lingers on at the fringes of Turkish politics. (Back in the 1970s, current

President Erdoğan wrote and performed in a theater play titled “Mas-Kom-Ya,” or Mason-Communist-Jew.)

This book by historian Dorothe Sommers looks at the development of Freemasonry in Ottoman territory through the 19th and early 20th century. Sommers particularly focuses on masonic lodges in Syria, but she also refers to their general situation around the empire. To some extent this is virgin territory, little researched up to now, and the book can only really scratch the surface. But there is still plenty to learn from it.

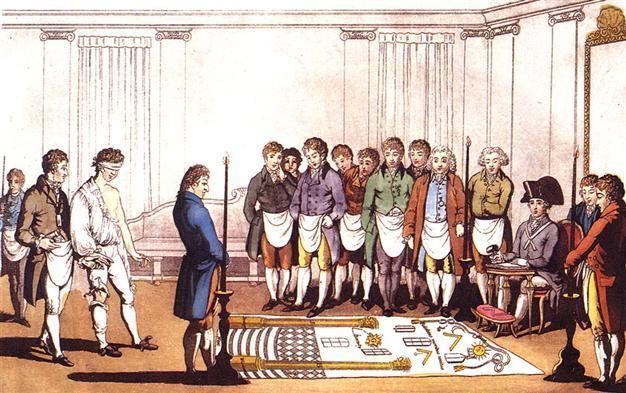

A secretive brotherhood largely made up of cosmopolitan elites emphasizing the “welfare of mankind” and partaking in arcane semi-religious rituals - it shouldn’t be surprising that so many conspiracy theories arose about global Freemasonry. There was another layer of intrigue in the Ottoman Empire, as Freemasonry was a European phenomenon that spread east with explicitly colonial structures through the 19th century. But masonic lodges in Ottoman territory quickly “went native” and adapted to local conditions. As elsewhere, the cadres who later filled the ranks of lodges in the Ottoman Empire generally belonged to the cosmopolitan middle and upper classes, often the vanguards of modernization in the eastern Mediterranean world. Lodges became a kind of guild system or social club for the local elites, who cultivated ideas of brotherhood, equality, toleration and reason, as well as less high-minded patronage networks of business and trade.

What makes Ottoman Freemasonry particularly intriguing is that it was an explicitly non-sectarian institution at a time when religious and national affiliations were becoming increasingly politicized. Ottoman Freemasons attempted to achieve what politics and religion were not able to manage: Uniting otherwise disparate minds, producing interreligious sociability, promoting social and moral emancipation. Through a non-religious community of men they sought to override political or religious cleavages, establishing a common denominator for communication and cooperation. The Bible was as welcome as the Quran. In the words of WS Nelson, a non-mason and former missionary in Syria at the end of the 19th century: “[Freemasonry] supplied to Syria a unifying principle, an organization in which all creeds and sects, Christian and Mohammedan alike, can find common ground and meet together as men and brothers whatever their religious differences.”

While many native Muslims were members of masonic lodges, many others were suspicious of an elite club with European origins preaching “civilization and fraternity.” Indeed, Freemasonry earned the opprobrium of religious leaders across the spectrum: Christian, Jewish and Muslim. Conspiracy theories flourished, with accusations about masons plotting to usurp world power resembling those about Jews in the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion.” As Sommer writes, “it was seen by many as a sinister, destructive sect that tried to govern the world in order to attack religious morality and to implement anarchy.”

The three central sections of Sommer’s book focus on lodges in Damascus, Beirut and Tripoli. While the depth of research is impressive, it might have been more rewarding to consider Freemasonry in the Ottoman Empire’s major cities further west like Istanbul, İzmir and Salonica. Some conspiracy theories today darkly claim that the young Mustafa Kemal Atatürk himself was active in Salonica’s Lodge Veritas, overseen by the French Grand Orient. Whatever the truth, it is certainly true that masonic lodges in Salonica played an active role in the city through the 19th and early 20th century.

Sommer admits that there is much more to research on the subject. But her book is still a worthy read. Of course it won’t attract the same attention as “Derin Tarih,” but it is definitely more informative.

‘Freemasonry in the Ottoman Empire: A History of the Fraternity and its Influence in Syria and the Levant’ by Dorothe Sommer (IB Tauris, 317 pages, £62)

‘Freemasonry in the Ottoman Empire: A History of the Fraternity and its Influence in Syria and the Levant’ by Dorothe Sommer (IB Tauris, 317 pages, £62) This book by historian Dorothe Sommers looks at the development of Freemasonry in Ottoman territory through the 19th and early 20th century. Sommers particularly focuses on masonic lodges in Syria, but she also refers to their general situation around the empire. To some extent this is virgin territory, little researched up to now, and the book can only really scratch the surface. But there is still plenty to learn from it.

This book by historian Dorothe Sommers looks at the development of Freemasonry in Ottoman territory through the 19th and early 20th century. Sommers particularly focuses on masonic lodges in Syria, but she also refers to their general situation around the empire. To some extent this is virgin territory, little researched up to now, and the book can only really scratch the surface. But there is still plenty to learn from it.