Fragile five or fab four

A high-up investment banker acquaintance was one of those who coined the term the fragile five in August 2013 to refer to five countries whose currencies had depreciated significantly during the summer, following worries that the Fed would start tapering its bond purchases.

A high-up investment banker acquaintance was one of those who coined the term the fragile five in August 2013 to refer to five countries whose currencies had depreciated significantly during the summer, following worries that the Fed would start tapering its bond purchases.The argument was that these countries had the highest external vulnerabilities and were likely to be bit by a currency crisis. The currencies, and in fact more generally financial assets, of Brazil, India, Indonesia, South Africa and Turkey indeed plunged again at the end of 2013 and beginning of 2014, as the Fed began its tapering.

Despite its popularity, the “fragile five” should not be seen as an ironclad classification. In fact, people were questioning it as early as last October, merely two months after its inception. For example, according to investment bank Nomura’s global emerging market risk index (GEMaRI), Turkey was the only country among the fragile five with a significant risk of currency crisis.

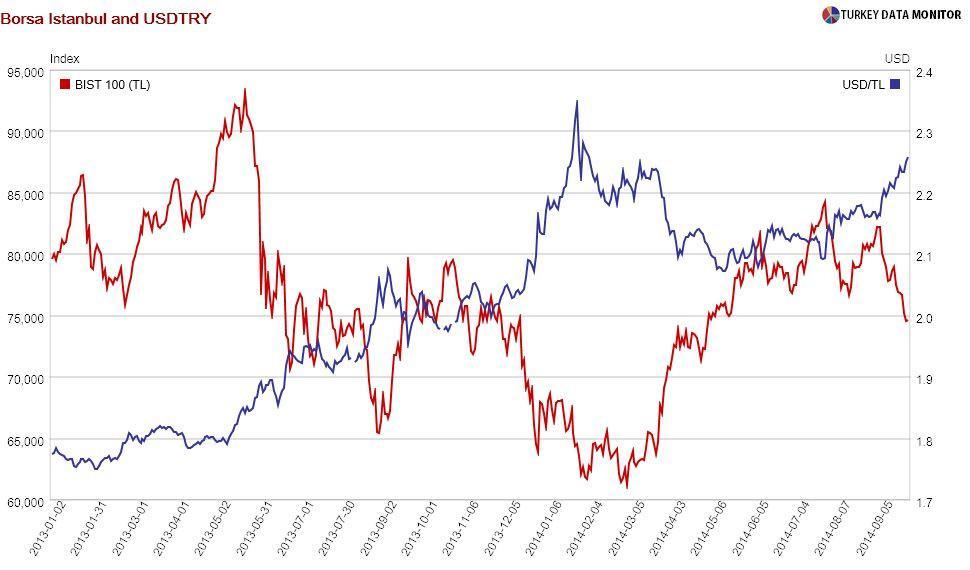

Nomura’s economists have identified a stock market plunge and deterioration in the current account deficit as the largest harbingers of a currency crisis. Other important signs, by order of importance, are a hike in the real interest rate of more than two percentage points over a quarter, rise in short-term external debt relative to reserves, a current account deficit larger than 3.5 percent of GDP and a reserves-to-imports ratio of less than 4.

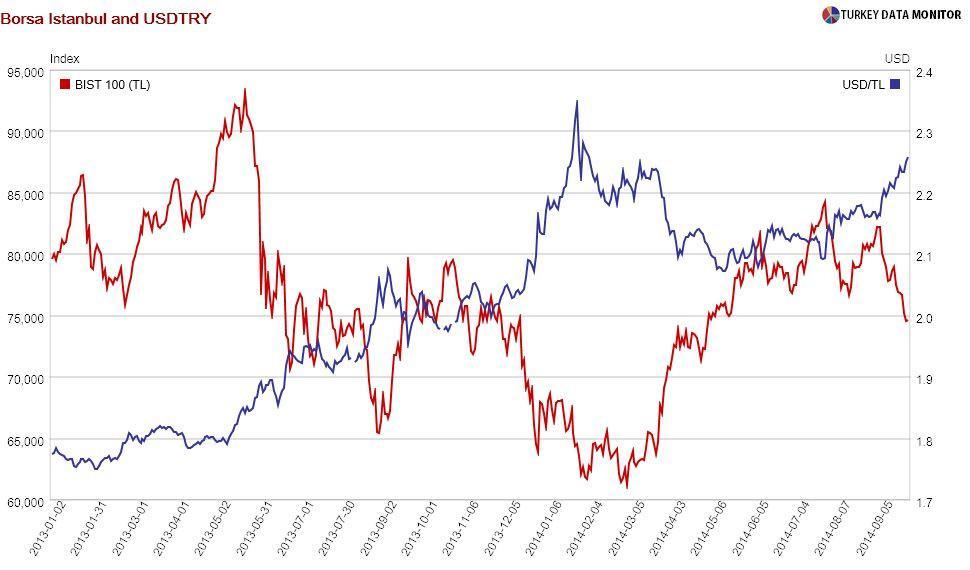

Turkey satisfied almost all of these conditions early in the year. But the Central Bank’s emergency rate hike at the end of January probably saved the country from a crisis rather than bringing about one, as well as earning it much-needed credibility. After that, equities recovered and the lira stabilized for a while.

Although I could not get hold of Nomura’s latest GEMaRI, I suspect Turkey has escaped their danger zone, as the current account deficit has been falling and the rise in short-term external debt to reserves has halted. A similar indicator by economics consultancy Capital Economics shows that while still with above average risk, Turkey is not one of the most vulnerable countries.

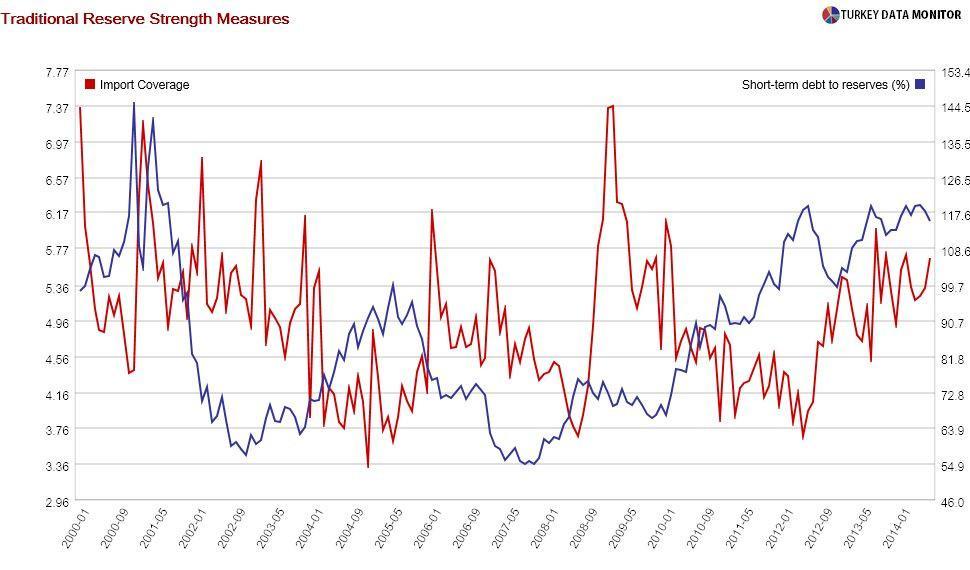

So why did Turkish stocks fall more than 7 percent this month? All emerging markets (EMs) have been affected from worries that an improving U.S. economy will prompt the Fed to start tightening soon and disrupt the capital flows to EMs. Among EMs, European stocks, hit by the conflict in Ukraine, have done worse. But the Turkish stock market underperformed in its region as well.

Turkey-specific factors, such as the conflicts in Iraq and Syria as well as worries over political stability and the rule of law in the country, could have played a role. Besides, you don’t get to see a government trying to bankrupt one of its banks every day. But Turkey is not the sole underperformer: There are four countries with large current account deficits whose assets plunged in September: Brazil, Colombia, South Africa and Turkey.

My banker acquaintance, who also happens to be Turkish, threw Turkey out of the fragile five a while back, when Turkish assets stabilized, and has been calling the rest the “fragile four” ever since. He may have got the number right, but the countries wrong.