Erdoğan holds key to Turkey's future, Hillary Clinton writes in memoir

ISTANBUL

Hillary Clinton's new memoir, “Hard Choices,” which many observers interpret as an unofficial kickoff of her prospective 2016 presidential campaign, dishes out plenty of material about key world leaders, but Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has a special place in the 656-page book published June 10.

Hillary Clinton's new memoir, “Hard Choices,” which many observers interpret as an unofficial kickoff of her prospective 2016 presidential campaign, dishes out plenty of material about key world leaders, but Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has a special place in the 656-page book published June 10.On issues from Cyprus to Armenia, Turkey is portrayed in the book as a difficult actor in negotiations, in which Clinton often set the tone as Washington’s top diplomat, who visited 112 countries in her tenure.

"None of our relationships in Europe needed more tending than Turkey, a country of more than 70 million people, overwhelmingly Muslim, with one foot in Europe and one in Southwest Asia," Clinton writes.

"The Turkish military, which saw itself as the guarantor of [Mustafa Kemal] Atatürk’s vision, intervened a number of times over the years to topple governments it saw as too Islamist, too left-wing, or too weak. Maybe that was good for the Cold War, but it delayed democratic progress,” she adds.

Clinton speaks in her book about how popular approval of her country had collapsed to just 9 percent in Turkey by 2007. "Unfortunately the Bush years took a toll on our relations," Clinton writes, adding that she visited Turkey as part of her first trip to Europe as secretary of state to connect with Turkish society, especially women.

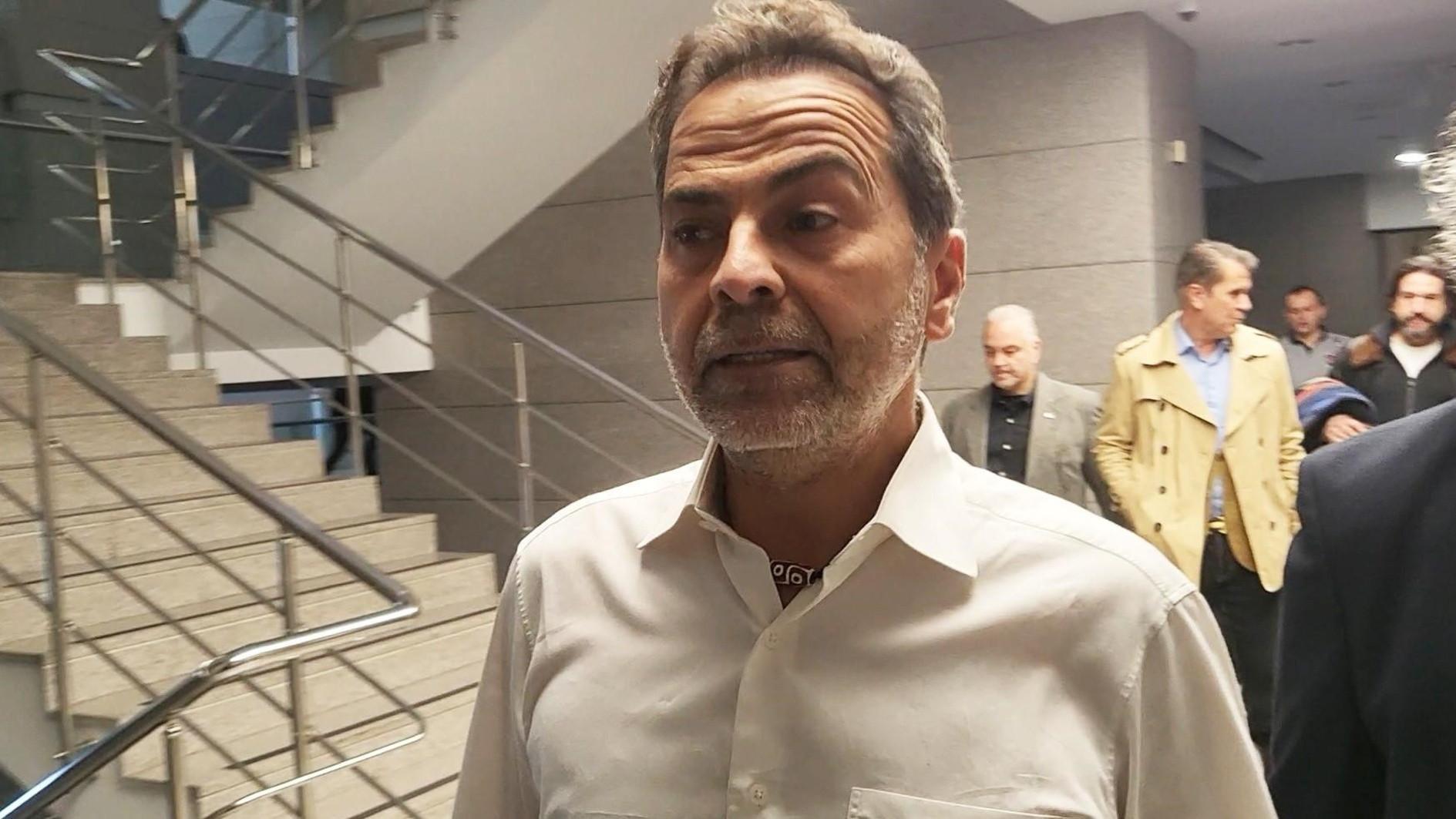

Clinton describes Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan as the man who "held the key to the future of Turkey and of our relationship."

"I first met him when he was mayor of Istanbul in the 1990s. He was an ambitious, forceful, devout, and effective politician," Clinton writes, stressing that Erdoğan "managed to gain a tighter grip on power than any of its civilian predecessors."

"Some of the changes under Erdoğan’s leadership were positive," she adds, hailing Ankara's reforms for EU membership and the ambition of her Turkish counterpart Ahmet Davutoğlu's “Zero Problems with Neighbors” foreign policy.

Problem with 'Zero Problems'

"Zero Problems sounded good, and in many cases it was constructive. But it also made Turkey overeager to accept a diplomatic agreement with its neighbor, Iran, that would have done little to address the international community’s concerns about Tehran’s nuclear program," Clinton writes.

"Despite positive developments under Erdoğan, there was growing cause for concern, even alarm, about his government’s treatment of political opponents and journalists. Decreasing room for public dissent raised questions about the direction Erdoğan was taking the country and his commitment to democracy," Clinton also writes, also giving an example from her personal contact with the Turkish PM.

"Erdoğan himself was very proud of his own accomplished daughters, who wore veils, and he asked my advice about one of them pursuing graduate studies in the United States,” she writes.

The prospective future U.S. president also touches on social tensions in Turkey in the book. "Corruption remained a massive problem, and the government was not able to keep up with the rapidly rising expectations of its increasingly worldly and middle-class citizens," she writes.

"In my four years as secretary, Turkey proved to be an important and at times frustrating partner," Clinton writes, particularly recalling the internationally mediated Zurich agreement in October 2009 between Turkey and Armenia as a "challenge."

Armenian FM Nalbandian 'balked'

"The next afternoon I left my hotel and headed to the University of Zurich for the ceremony. But there was a problem. [Edward] Nalbandian, the Armenian minister, was balking. He was worried about what Davutoğlu planned to say at the signing and suddenly was refusing to leave the hotel. It seemed as if months of careful negotiations might fall apart," Clinton writes, adding that she "worked the phones" and convinced both of her colleagues to "sign the document, make no statements, and leave."

Although neither country has ratified the protocols yet, Clinton states that she "still hopes for a breakthrough.”

A few months after the Zurich agreement, Turkey was once again on Clinton's crisis agenda, when Israeli commandos raided the Mavi Marmara ship from Turkey carrying pro-Palestinian activists trying to break the Israeli blockade of Gaza, killing 10 Turkish citizens.

Clinton writes that she received an urgent call from her Israeli counterpart, Ehud Barak, and warned him that “there will be unforeseen repercussions." The next day, Davutoğlu came to see Clinton and they talked for more than two hours.

'Turkey might declare war on Israel'

"He was highly emotional and threatened that Turkey might declare war on Israel. 'Psychologically, this attack is like 9/11 for Turkey,' he said, demanding an Israeli apology and compensation for the victims. 'How can you not care?' he asked me. 'One of them was an American citizen!' I did care – quite a lot – but my first priority was to calm him down and put aside all this talk of war and consequences,” she writes.

Clinton later presents Israel's apology in 2013 as the final product of her "efforts to convince Bibi [Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu]" for the remainder of her tenure.

"The Turks and Israelis are still working to rebuild the trust lost in this incident," she adds.