Don’t do business, mind the (gender) gap

Everyone is discussing the impact of U.S. monetary policy on Turkish assets. They are missing the forest in favor of the trees: Two reports released this week highlight the real weaknesses of the Turkish economy.

“

İş yapma” can mean either “doing business” or “don’t do business” in Turkish. The World Bank’s latest “Doing Business” report, which was

released on Oct. 29, explains this double meaning. In the report’s rankings, which are formed by analyzing “regulations that apply to an economy’s businesses during their life cycle, including start-up and operations, trading across borders, paying taxes and resolving insolvency,” Turkey is 55th among 189 countries.

In a

press release going over the results,

Martin Raiser, the Bank’s Country Director for Turkey, sounded positive, underlining that Turkey’s rank was “slightly down from 51 last year” and the country scored “largely as expected for an upper middle-income country.” He explained Turkey’s worsening relative position with the increase in minimal capital requirements in 2013, which made starting a business

considerably more difficult.I personally do not share Raiser’s optimism. Turkey has been stuck at more or less the same rank ever since the first Doing Business report was published 12 years ago, roughly when the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power. But maybe he was comparing the results to those of the other report of the week, the World Economic Forum’s

Global Gender Gap Report.This study measures the size of the gender equality gap and ranks countries in four areas: Economic participation and opportunity, education, political empowerment and, health and survival. Turkey is ranked 125th, dropping from last year’s 120th, mainly thanks to the increase in covered countries from 136 to 142.

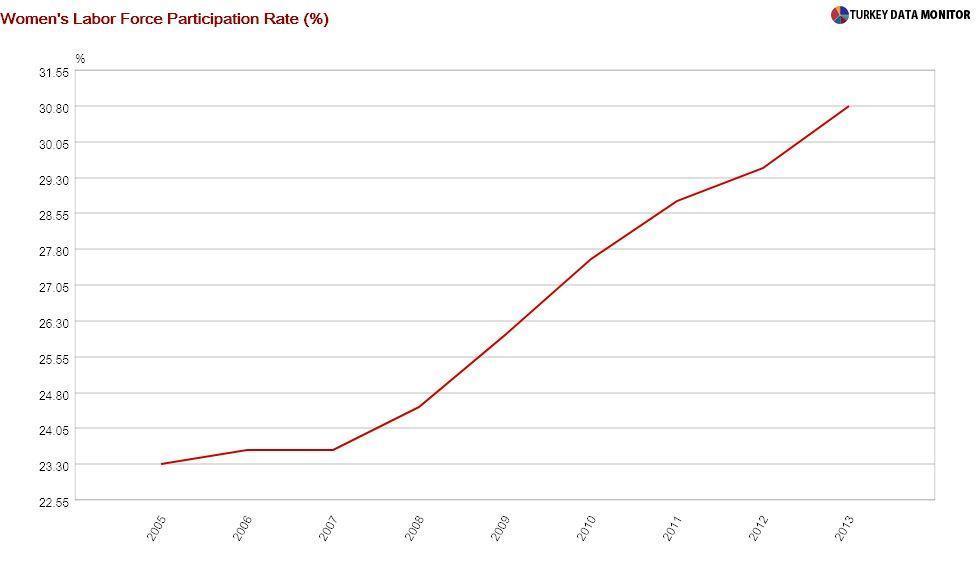

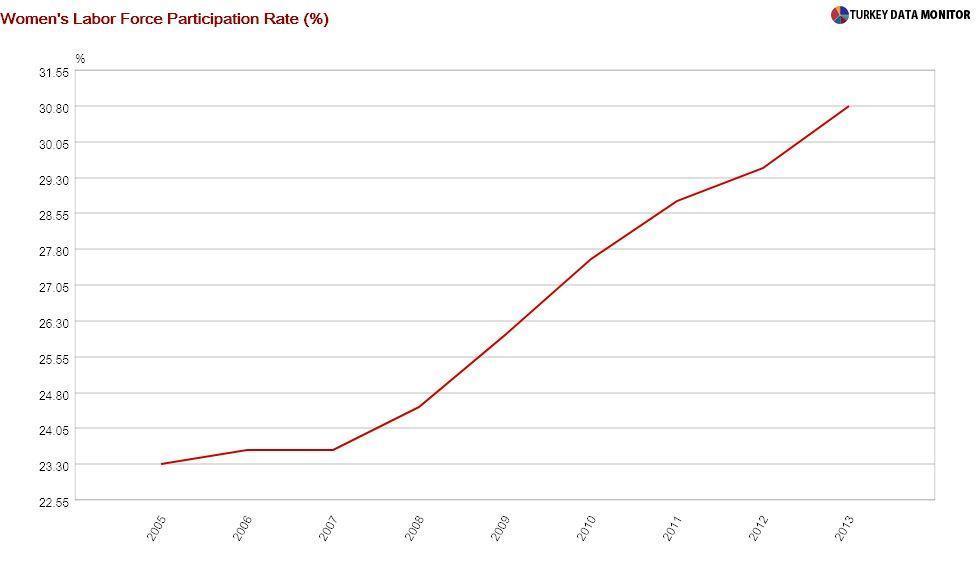

Despite the steady improvement in its overall score since 2011,

the report notes, “Turkey is still the lowest performing country from the OECD on the overall index; and it is the lowest performing country from its region on the economic participation and opportunity subindex, ranking 132nd.” Among upper middle-income countries, it is ranked 36th out of 40 countries.

While some link this performance to cultural and religious factors, Turkey compares unfavorably to other Muslim countries as well. The answer is more in enacting the right policies. For example, although the country still “ranks 128th overall on the labor force participation indicator,” women’s LFP rate rose after their social security premium contributions

were reduced in 2008.

However, I am not sure if the government genuinely wants to narrow Turkey’s gender gap. After all,

policies such as financial support to take care of the elderly at home and tax exemptions for self-employed women working from home show incentives are provided in a way to keep women at home.

President Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan probably finds working women incompatible with his goal of having every healthy Turkish woman give birth to

at least three children. Other great leaders have pushed for

similar policies, so he may be right.

Everyone is discussing the impact of U.S. monetary policy on Turkish assets. They are missing the forest in favor of the trees: Two reports released this week highlight the real weaknesses of the Turkish economy.

Everyone is discussing the impact of U.S. monetary policy on Turkish assets. They are missing the forest in favor of the trees: Two reports released this week highlight the real weaknesses of the Turkish economy.